Introduction

Zombies have shambled through human storytelling for centuries, evolving from Haitian spiritual beliefs into one of horror's most enduring and versatile monsters. For writers, the zombie offers something unique: a blank canvas that can represent consumerism, conformity, pandemic fears, or simply pure survival terror.

This guide synthesizes historical research, game design mechanics, and narrative craft into practical tools you can use immediately. Whether you're writing interactive fiction, a novel, or a screenplay, you'll find the foundations you need to build authentic, engaging zombie worlds.

The Zombie's Secret Power

Unlike vampires or werewolves, zombies have no inherent personality. They're a force of nature—which means the story is never really about the zombies. It's about the survivors, their choices, and what humanity looks like when civilization crumbles.

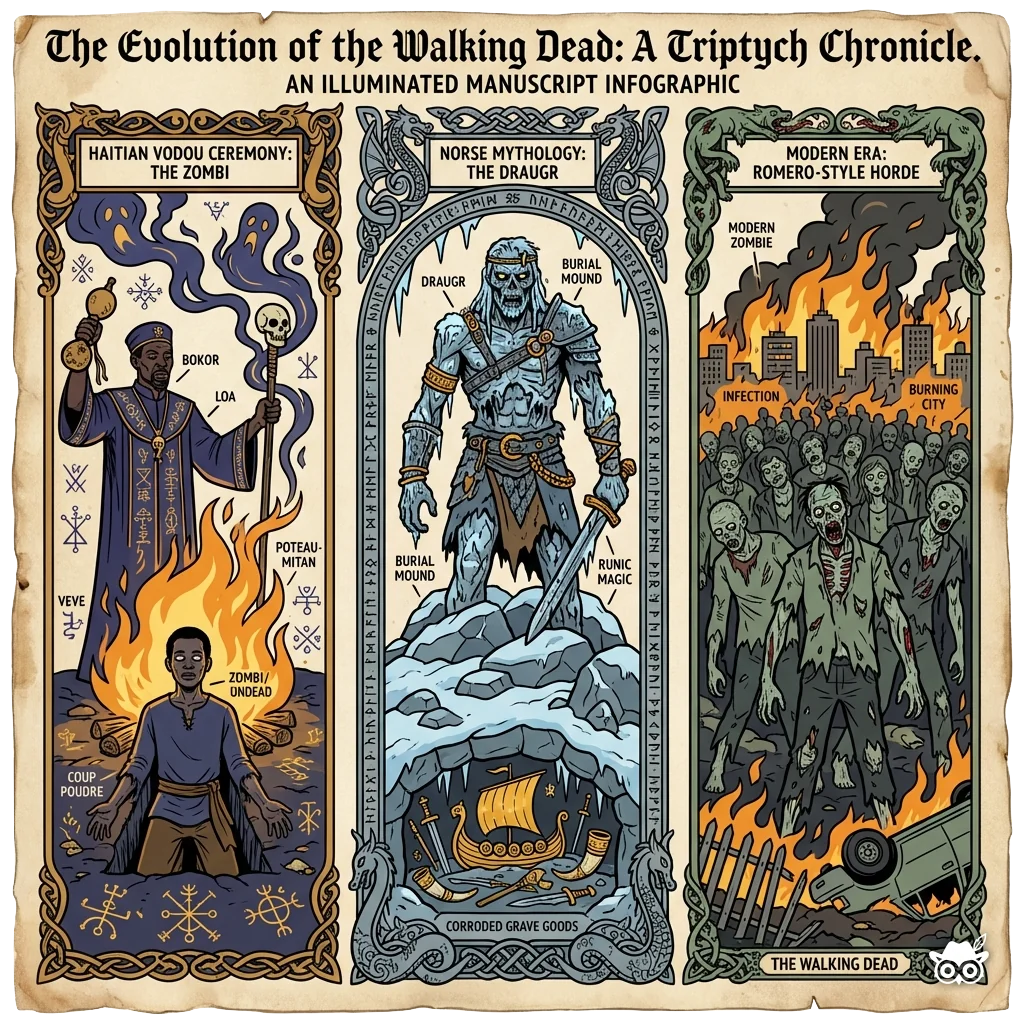

The History of Zombies

Understanding where zombies come from enriches your writing and opens creative possibilities beyond the standard Hollywood shambler. The zombie has a complex, often troubling history rooted in slavery, colonialism, and spiritual belief.

Haitian Vodou: Where It All Began

The original "zonbi" wasn't a flesh-eating monster—it was something far more terrifying to those who believed in it. In Haitian Vodou, a zonbi is a person whose soul has been captured by a sorcerer called a bokor, rendering them a will-less slave. The fear wasn't of zombies; it was of becoming one.

Two Types of Zonbi

Zonbi Astral: A captured spirit stored in a bottle, which could be sold for luck or protection. Zonbi Corps Cadavre: A physical body animated without its soul—the version that eventually inspired Hollywood.

The most famous alleged zombie case is Clairvius Narcisse, who was declared dead in Haiti in 1962 and buried the next day. In 1980, he returned to his village, claiming he'd been exhumed, drugged, and forced to work on a sugar plantation. His brother allegedly arranged his zombification as punishment for a family land dispute.

African Folklore Roots

The word "zombie" itself traces back to Central and West African languages, brought to Haiti through the transatlantic slave trade. Understanding these linguistic roots reveals how deeply African spirituality shaped Haitian Vodou.

| Term | Language | Meaning | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| nzambi | Kongo | Spirit, god, or the supreme deity | Congo Basin |

| zumbi | Kimbundu | Fetish or ghost | Angola |

| ndzumbi | Mitsogho | Corpse | Gabon |

| mvumbi/nvumbi | Kongo | Corpse or walking dead | Congo Basin |

In Kongo cosmology, Nzambi a Mpungu was the supreme creator deity—distant but all-powerful. When enslaved Africans were forced to adopt Catholicism in Haiti, they merged their traditional beliefs with Catholic saints in a process called syncretism. The Christian God became associated with Nzambi, while lesser spirits (lwa) took the forms of Catholic saints.

Nkisi and Zonbi Astral

The Kongo concept of nkisi—spirit containers or fetishes that housed spiritual power—parallels the Haitian zonbi astral (captured souls in bottles). Both traditions believed spirits could be bound to physical objects and controlled by those who knew the proper rituals. This wasn't devil worship, as colonial observers claimed, but a sophisticated spiritual technology for managing relationships with the ancestral and spirit worlds.

The creation of Vodou itself was an act of cultural resistance. When slave masters banned African religious practices, enslaved people developed a hybrid system that appeared Catholic on the surface while preserving African spiritual frameworks. The zombie—a person stripped of will and autonomy—became a powerful metaphor for slavery itself.

Ancient Roots Across Cultures

The idea of the dead returning isn't unique to Haiti. The Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2700 BCE) contains the oldest recorded threat of the dead rising to eat the living. When Gilgamesh rejects the goddess Ishtar, she threatens to "bring up the dead to consume the living" and "make the dead outnumber the living."

The Colonial Transformation

The zombie we know today was shaped by the American military occupation of Haiti (1915-1934). Returning soldiers and journalists brought back "exotic stories" that painted Haiti as a land of devil worship and living dead—narratives that helped justify the occupation to American audiences.

William Seabrook's 1929 book The Magic Island was the first popular English-language text to describe zombies as reanimated corpses. Though only 12 pages addressed zombies directly, those pages defined them as "a soulless human corpse, still dead, but taken from the grave and endowed by sorcery with a mechanical semblance of life." This directly inspired the 1932 film White Zombie.

| Haitian Zonbi | Western Zombie |

|---|---|

| Victim to be pitied | Monster to be feared |

| Individual targeted for transgression | Random mass affliction |

| Created by sorcerer's magic | Often caused by virus or radiation |

| Mindless slave laborer | Flesh-eating predator |

| Under bokor's control | Autonomous hunters |

| Slavery metaphor | Apocalypse/contagion metaphor |

Use History for Depth

Consider incorporating elements of the original zonbi mythology. A villain who controls zombies, a cure that "releases" the soul, or zombies who can be freed from their state all add layers beyond the standard apocalypse setup.

The Science of Zombie Powder

The Clairvius Narcisse case caught the attention of Harvard-trained ethnobotanist Wade Davis, who traveled to Haiti in the early 1980s to investigate whether there was a pharmacological explanation for zombification. His findings, published in The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985), proposed a scientific mechanism behind the folklore.

Wade Davis's Zombie Powder Theory

Davis proposed that bokors used a powder called coup de poudre (literally "blow of the powder") containing two key ingredients: tetrodotoxin from pufferfish, which can induce a death-like state of paralysis and extremely slowed vital signs, and Datura stramonium (jimsonweed), a powerful hallucinogen that causes amnesia, disorientation, and extreme suggestibility. According to the theory, victims would be declared dead, buried, exhumed after oxygen deprivation caused brain damage, then kept in a compliant state through continued drugging and psychological manipulation.

The tetrodotoxin theory was elegant: in low doses, this neurotoxin blocks sodium channels in nerve cells, causing paralysis while leaving the victim conscious but unable to move or speak. In Haiti's hot climate, burial occurs within 24 hours of death—theoretically allowing time for a poisoned person to be buried alive, then recovered before actual death occurred.

Problems with the Zombie Powder Theory

Davis's theory faced significant scientific criticism. When toxicology labs analyzed the powder samples he brought back, they found little to no tetrodotoxin—certainly not enough to induce a death-like state. Other researchers who tried to replicate his findings discovered that many of the "pufferfish" specimens Davis collected were actually species that don't produce tetrodotoxin at all. The doses required to achieve the described effect would be nearly impossible to calibrate with folk preparation methods—too little and nothing happens, too much and the victim dies.

Davis defended his work by pointing out that folk medicine formulas are inherently variable—not every batch would have the same potency, and bokors would refine their techniques through trial and error over generations. He also emphasized that zombification was primarily a cultural phenomenon, not purely pharmacological. The psychological impact of the ritual, combined with the victim's belief in Vodou and the bokor's power, might be as important as any drug in creating compliant behavior.

The Power of Ambiguity

The unresolved scientific debate around zombie powder makes excellent story material. Is your zombie-creating mechanism purely chemical, purely psychological, or some combination? Leaving room for uncertainty can be more unsettling than definitive explanations. Consider how the doubt around the Narcisse case persists precisely because it can't be fully proven or disproven.

The Evolution of Zombie Media

While Romero's Night of the Living Dead is justifiably credited with creating the modern zombie, the path from Haitian folklore to flesh-eating hordes was paved by decades of pulp literature, horror comics, and genre-defining films.

Early Literature: The Weird Fiction Era

Before zombies shambled across cinema screens, they lurched through the pages of pulp magazines. H.P. Lovecraft's serialized story "Herbert West—Reanimator" (1922) appeared in Home Brew magazine as a science fiction horror parody of Frankenstein. While not traditional zombies, Lovecraft's reanimated corpses established the template of death conquered by science gone wrong.

Weird Tales Magazine

From 1923 to 1954, Weird Tales was the most important fantasy magazine in America. It featured Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard (whose story "Pigeons from Hell" included zuvembies—zombie-like creatures), and countless other writers who shaped horror fiction. These pulp magazines normalized supernatural horror for mainstream audiences.

Richard Matheson's I Am Legend (1954) deserves special attention. Though technically about "vampires," it established virtually every convention of modern zombie fiction: a scientific/disease origin, worldwide pandemic, last survivor narrative, and the complete collapse of civilization. The infected in I Am Legend behave far more like modern zombies than traditional vampires—mindless, plague-spreading, and overwhelming in numbers.

The Comics Code Kills the Undead

During the early 1950s, EC Comics published some of the most inventive horror stories in American history through titles like Tales from the Crypt, Vault of Horror, and Haunt of Fear. These comics regularly featured zombies, often with darkly ironic twist endings.

The Comics Code Authority of 1954

Public outcry over horror comics led to the Comics Code Authority, which banned the words "terror" and "horror" from comic titles and explicitly prohibited "scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism." This ban on zombies lasted until the late 1980s, creating a 30-year gap in zombie comics.

Beyond Romero: The Post-1968 Zombie Renaissance

While George Romero created the template with his "Dead" films, other filmmakers expanded and subverted zombie conventions in surprising ways:

| Film | Year | Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| The Evil Dead | 1981 | Introduced "shaky cam" technique and demonic possession (Deadites aren't technically zombies but demon-possessed corpses) |

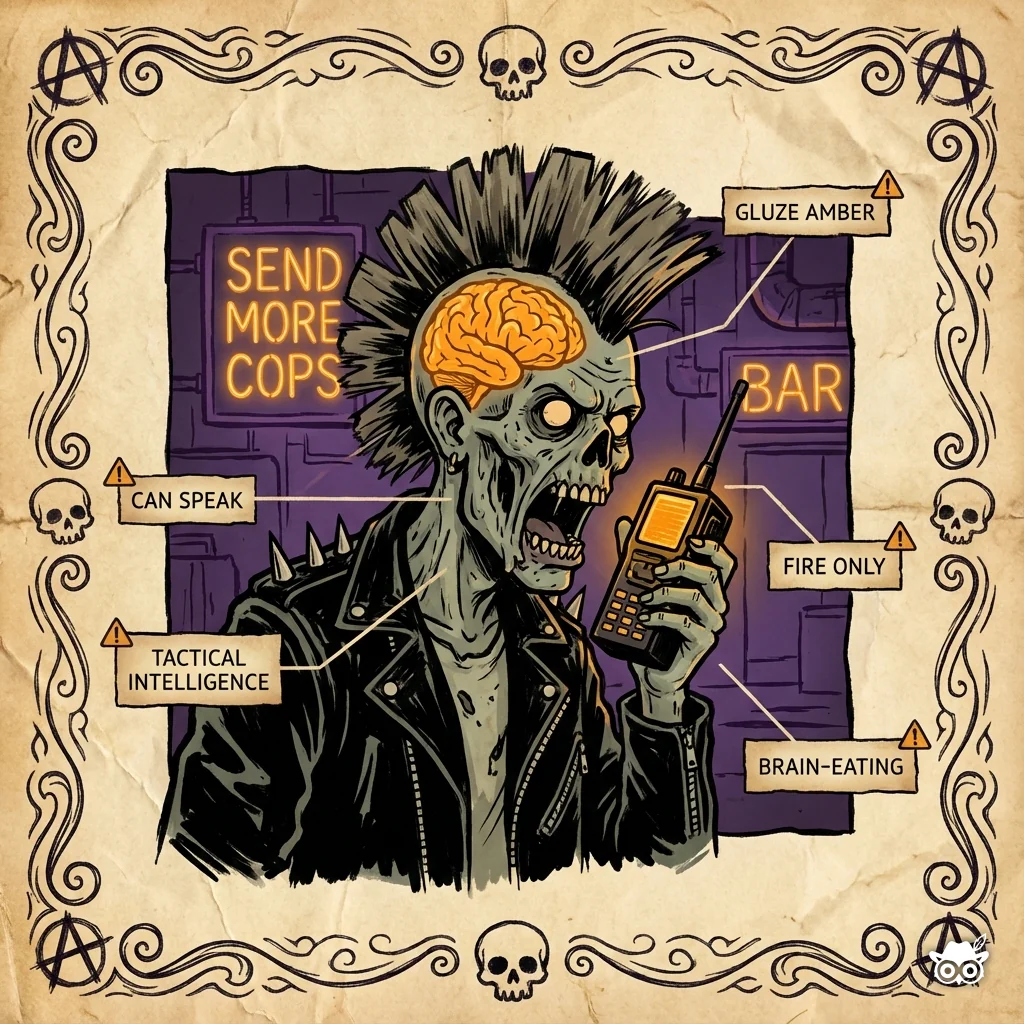

| Return of the Living Dead | 1985 | Introduced the iconic "BRAINS!" cry, talking zombies ("Send more cops!"), and zombies that can't be killed by headshots |

| Dead Alive/Braindead | 1992 | Peter Jackson's pre-Lord of the Rings splatter-comedy, considered the goriest film ever made (300+ liters of fake blood used in the finale alone) |

Learn from the Innovators

Return of the Living Dead succeeded by breaking Romero's rules: its zombies talk, run, can't be killed by destroying the brain, and are played for dark comedy. Don't be afraid to challenge established zombie conventions—some of the best zombie fiction comes from asking "what if the rules were different?"

The Top 10 Zombie Types

Click each type to explore their characteristics, origins, and writing applications.

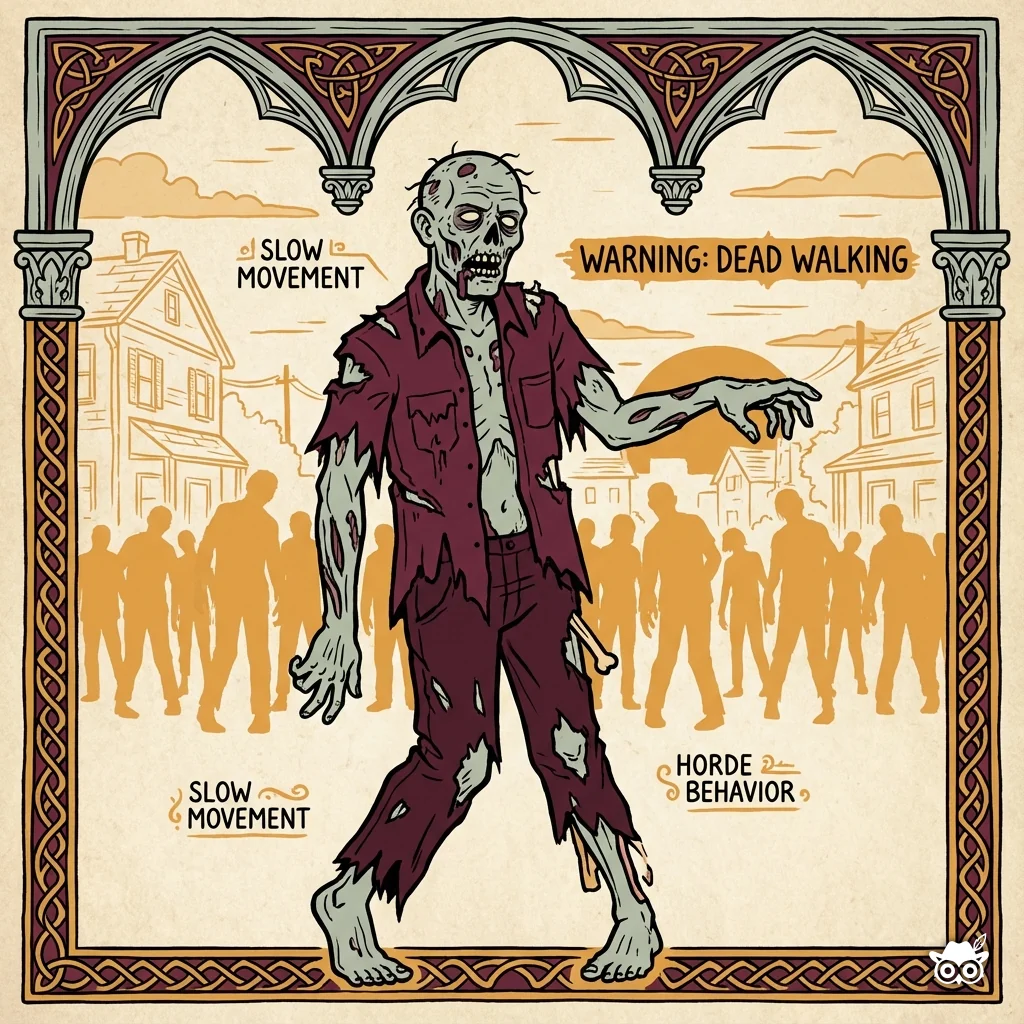

Romero Shambler

The Romero Shambler

Origin: Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The classic. Slow, relentless, and unstoppable in numbers. George Romero's creation established the rules that defined the genre for decades.

Writing Applications

- Threat comes from numbers and attrition, not individual encounters

- Perfect for siege narratives and resource management stories

- Slow pace allows character development between action

- Human conflicts often become the real danger

Fast Runner

The Fast Runner

Origin: 28 Days Later (2002), Dawn of the Dead remake (2004)

Sprinting, screaming, and terrifying. These zombies reinvigorated the genre by making every encounter immediately life-threatening.

Writing Applications

- Creates constant tension—nowhere is safe for long

- Works well for action-focused narratives

- Stealth becomes crucial—noise management matters

- Single zombie can be a genuine threat

Rage Infected

The Rage Infected

Origin: 28 Days Later (2002), REC series

Technically still alive—humans transformed by a virus into mindless killing machines. They can starve, bleed out, and die from their own infection.

Writing Applications

- Creates moral complexity—they're still human

- Waiting out the infection becomes a viable strategy

- Near-instant transformation creates paranoid tension

- Medical/cure plots are more plausible

Cordyceps

The Cordyceps Infected

Origin: The Last of Us (2013)

Based on real parasitic fungi, these infected evolve through terrifying stages as the fungus consumes and transforms their bodies.

Writing Applications

- Multiple enemy types from one infection source

- Clickers use sound—creates stealth gameplay opportunities

- Spores add environmental hazards to locations

- Scientific basis grounds the horror in reality

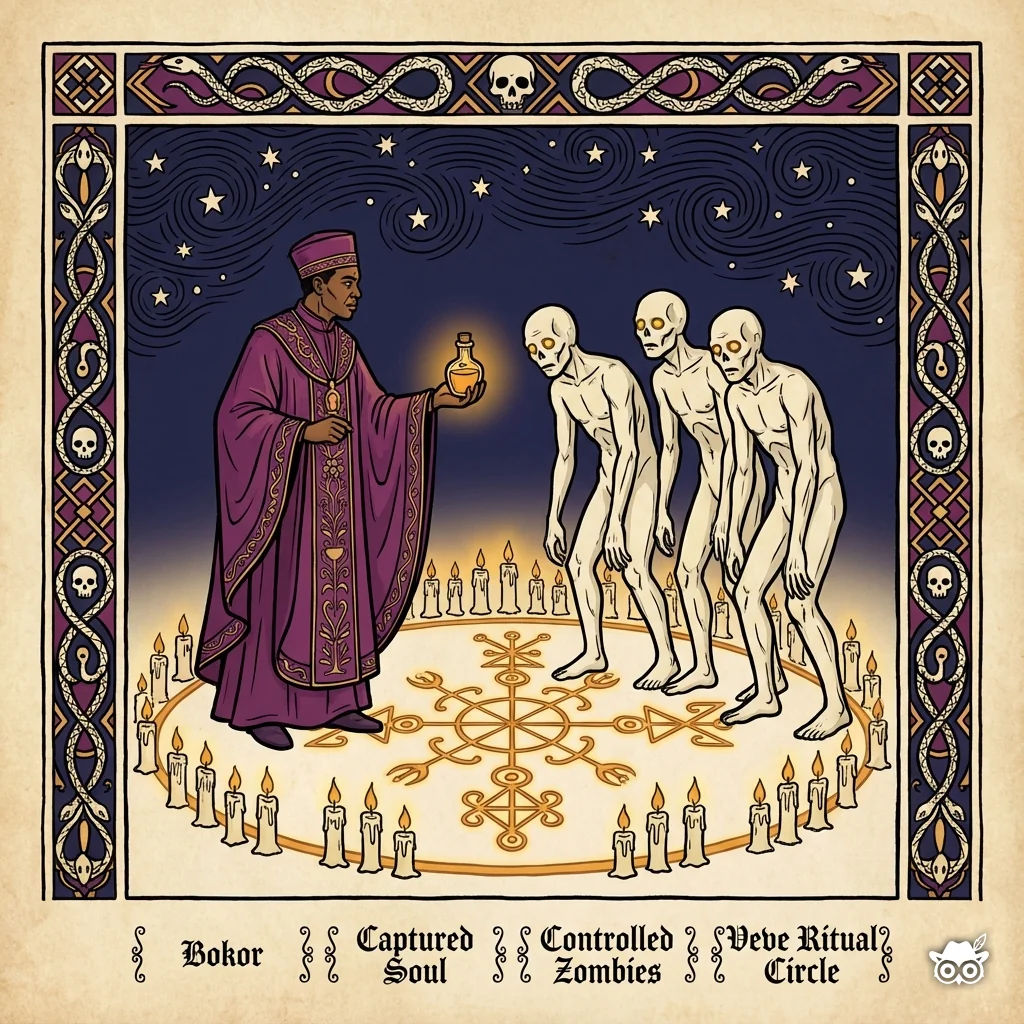

Voodoo

The Voodoo Zombie

Origin: Haitian Vodou tradition

The original. Not a flesh-eating monster but a soulless slave, created through ritual magic and controlled by a bokor. Can potentially be freed.

Writing Applications

- Central villain (the bokor) gives story focus

- Cure/release is possible—rescue missions make sense

- Rich cultural mythology to draw from

- Zombies as victims creates different moral dynamic

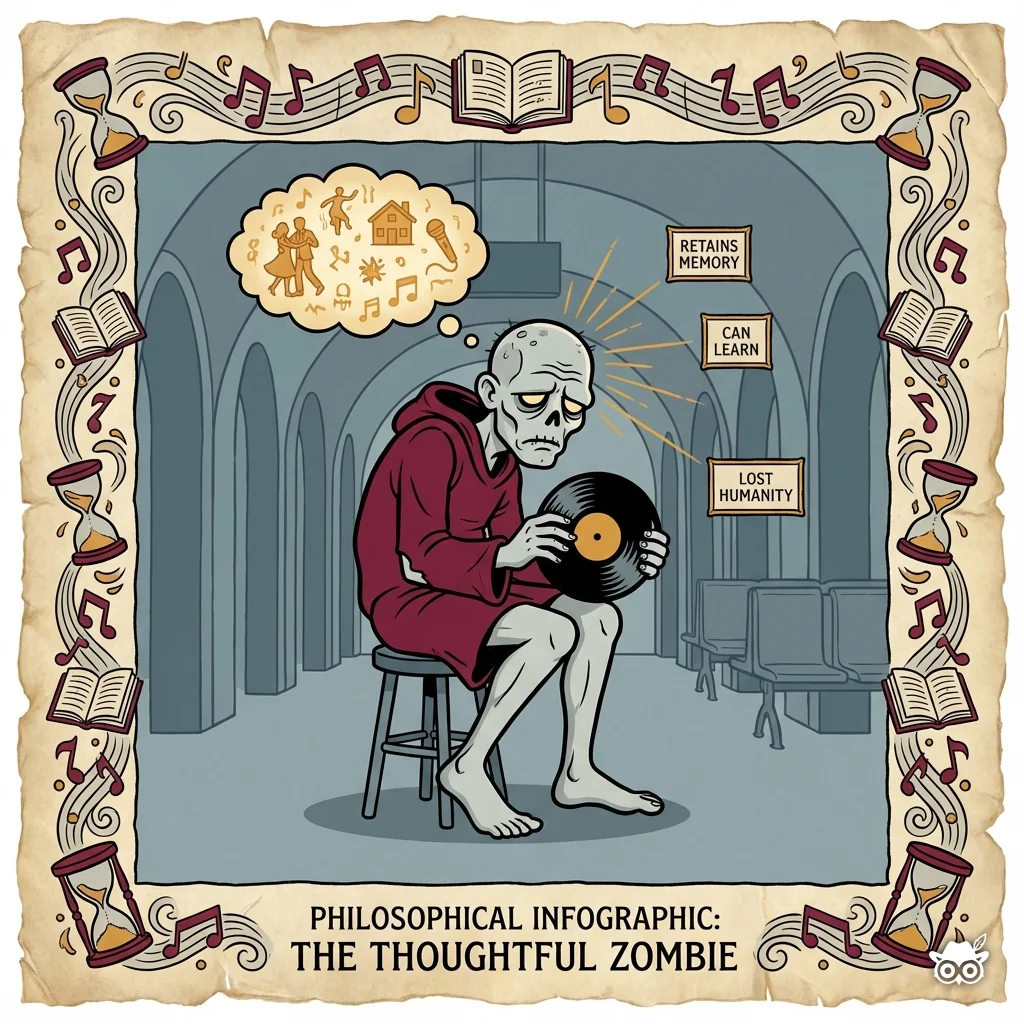

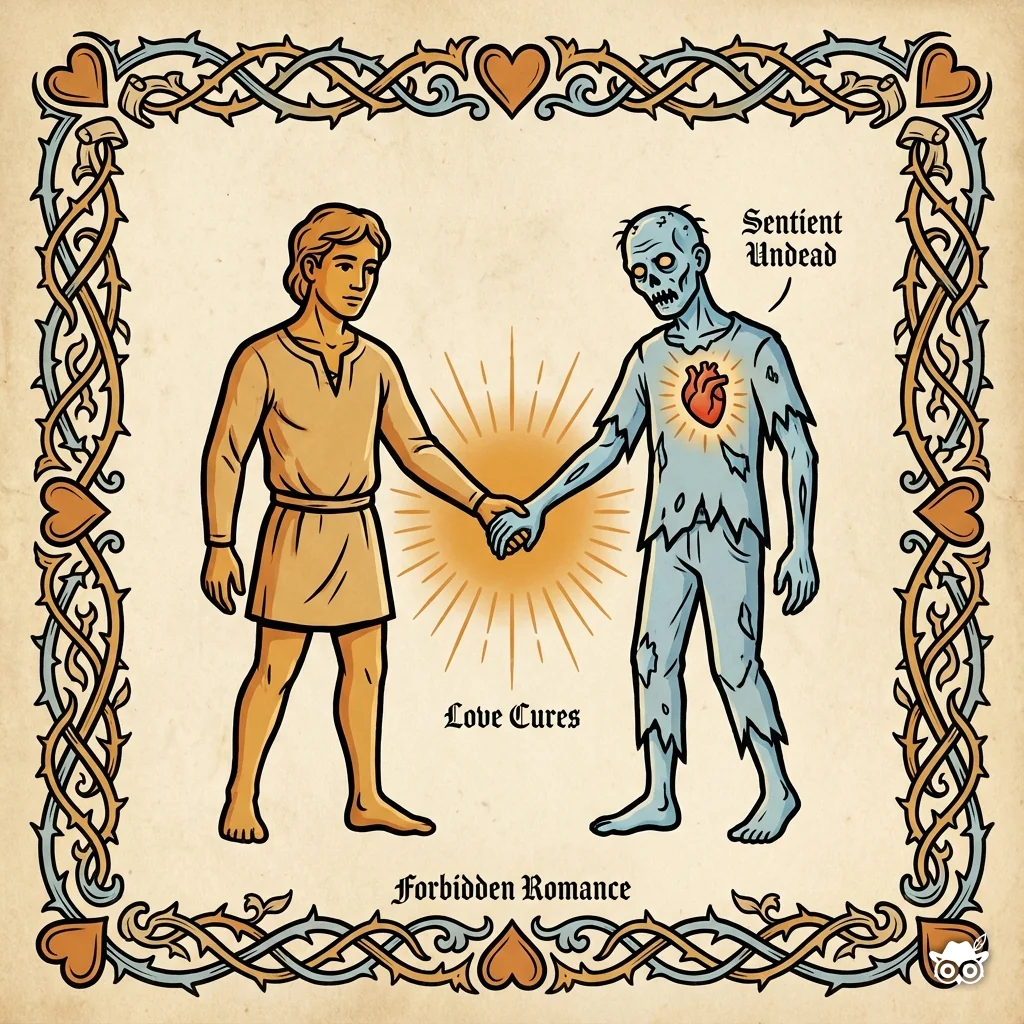

Intelligent

The Intelligent Zombie

Origin: Day of the Dead (1985), Warm Bodies (2010)

Zombies that retain or develop cognition—from Bub's learned behaviors to R's internal monologue. They remember, they feel, they might even be redeemable.

Writing Applications

- Opens philosophical questions about consciousness

- Zombie POV narratives become possible

- Creates genuine character development for undead

- Rehabilitation/coexistence themes emerge

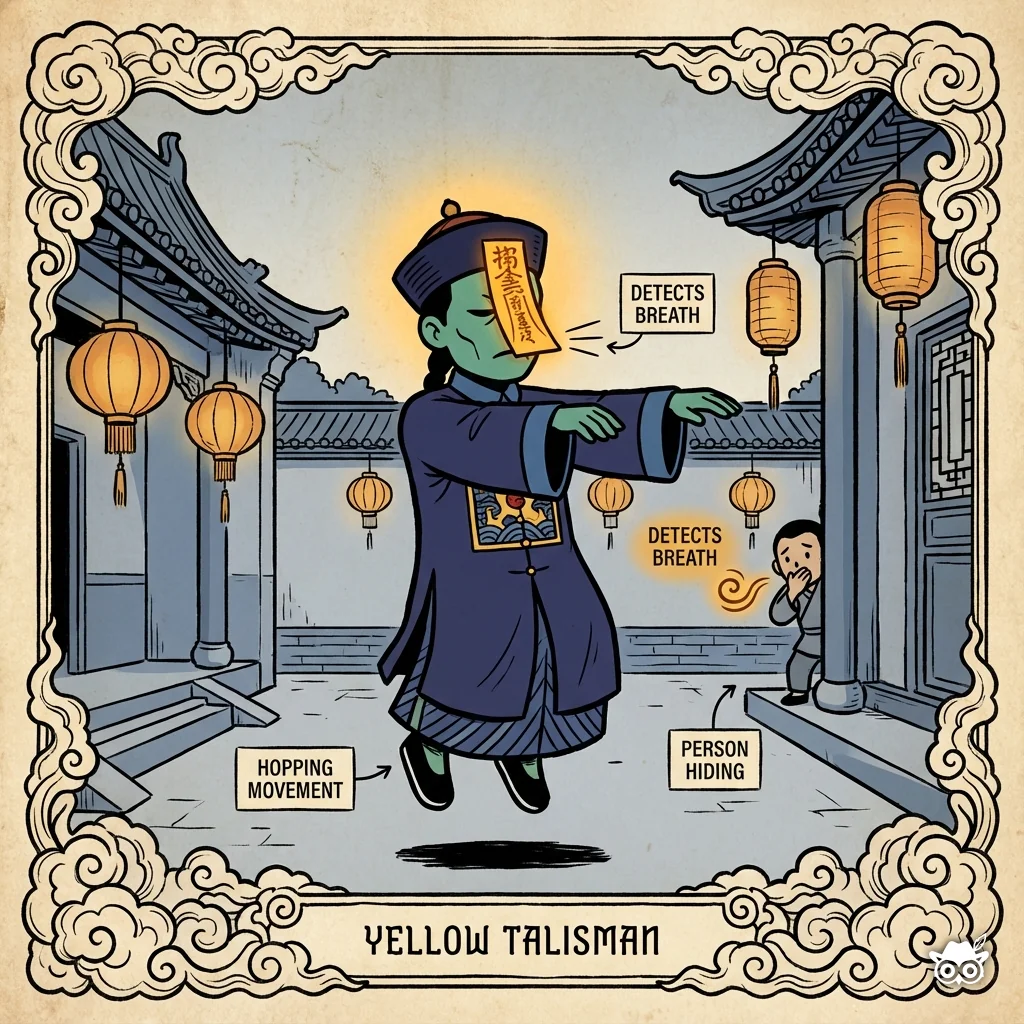

Jiangshi

The Jiangshi

Origin: Chinese folklore, Qing Dynasty

The "hopping vampire"—a reanimated corpse that moves by hopping due to rigor mortis. Blind, but detects prey by their breath. Unique vulnerabilities create distinctive encounters.

Writing Applications

- Breath-holding stealth creates unique tension

- Environmental puzzles using mirrors, barriers, sticky rice

- Counting compulsion can be exploited for escape

- Talismans work as consumable defensive items

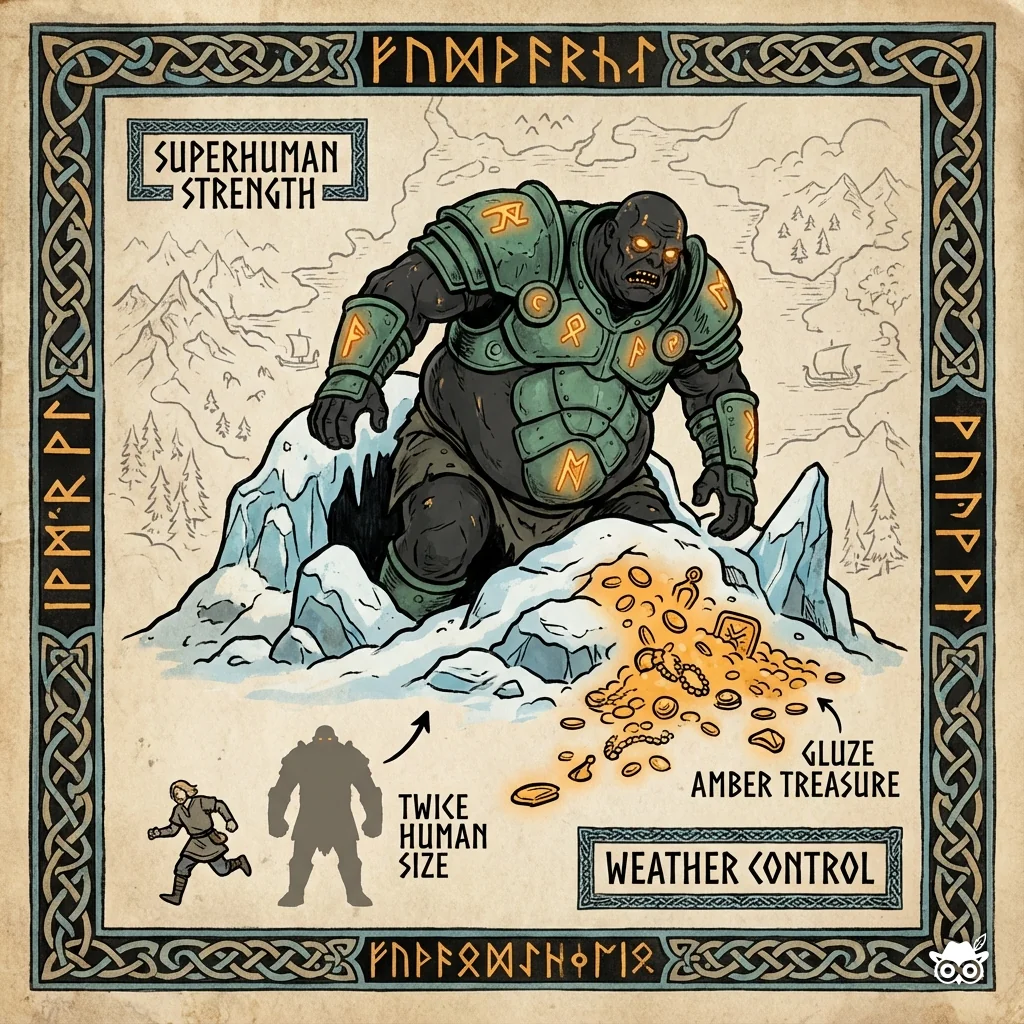

Draugr

The Draugr

Origin: Norse mythology, medieval sagas

Not ghosts but corporeal revenants—bloated, blackened, superhumanly strong, and capable of growing in size. They guard burial mounds and their treasure with terrifying power.

Writing Applications

- Works as "boss encounter" guardian of valuable locations

- Infectious death expands the threat naturally

- Curses create lasting consequences for survivors

- Perfect for fantasy or historical settings

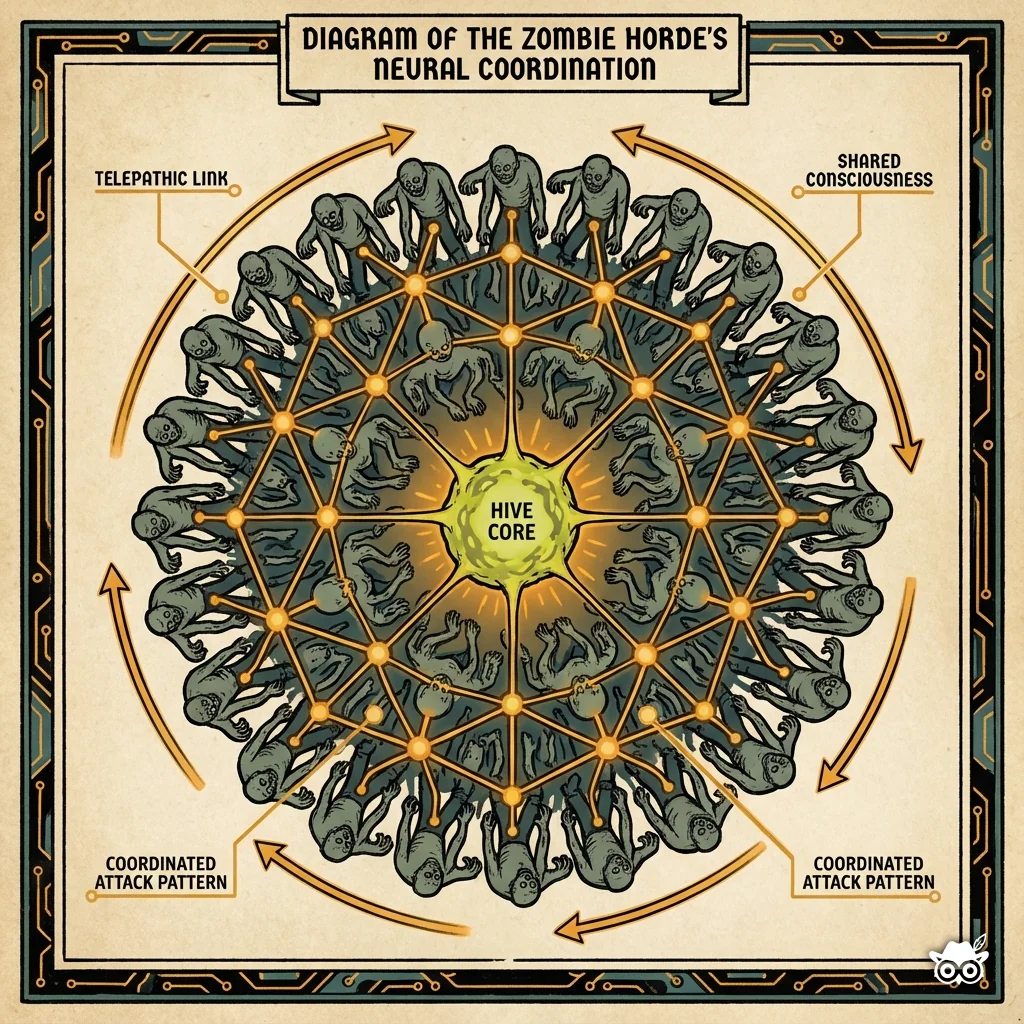

Hive Mind

The Hive Mind Zombie

Origin: Various games and novels

Connected telepathically or through a central consciousness. They coordinate attacks, share information, and may be controlled by an "alpha" or queen. Killing individuals means nothing if the network persists.

Writing Applications

- Creates escalating tactical challenges

- Goal-oriented plot: find and destroy the source

- Stealth is harder when one zombie's sight alerts all

- Potential for communication/negotiation with hive mind

Return Dead

The "Return" Zombie

Origin: Return of the Living Dead (1985)

The ones who scream "BRAINS!" Fast, intelligent enough to speak and strategize, and nearly impossible to kill—headshots don't work; only fire destroys them completely.

Writing Applications

- "Send more paramedics" tactical zombies create unique threat

- Removes headshot safety net—changes all combat

- Fire becomes essential, creating resource pressure

- Works well for dark comedy or punk aesthetics

Zombie Taxonomy

Zombies are more than just shambling corpses. Understanding how to categorize them by origin, behavior, and physical state helps you craft consistent rules for your fictional world and create unique variations that serve your story's themes.

By Origin/Cause

The source of zombification profoundly shapes your story's tone, rules, and whether a cure is possible. Each origin brings different narrative possibilities.

Viral/Infectious

Biological viruses that spread through bites, fluids, or airborne transmission. This is the most "grounded" origin, allowing for scientific explanations and medical research plotlines.

- Solanum (World War Z): 100% fatal, 100% conversion rate. Incubation varies but reanimation is inevitable. Creates slow, persistent threat.

- T-Virus (Resident Evil): Creates mutations beyond basic zombification. Different hosts produce different results—dogs, crows, even plant life. Umbrella Corporation's bioweapon origins add conspiracy elements.

- Rage Virus (28 Days Later): Not true undead—victims are still alive, just infected with weaponized rage. Incubation in seconds, death by starvation in weeks. Fast, aggressive, and terrifying.

- Knox Infection (Project Zomboid): Unknown origin, airborne with bite transmission accelerating turn time. Everyone is infected; only bite determines when you turn. Creates paranoia and inevitability.

Viral Origin Advantages

Allows for medical research plots, vaccine race storylines, and discussion of patient zero. Scientists remain relevant characters. However, it also invites readers to question scientific plausibility—be prepared to hand-wave some details or embrace the speculation.

Parasitic/Fungal

Organisms that hijack the host's body for their own reproduction. Often inspired by real-world parasites like Ophiocordyceps, these infections create disturbing body horror and progressive transformation stages.

- Cordyceps Infection (The Last of Us): Progresses through distinct stages over months/years:

- Runners (Days 0-14): Recently infected, still mostly human

- Stalkers (Weeks 2-12): Fungal growth beginning, use stealth tactics

- Clickers (Months 12+): Blind, use echolocation, fungal plates armor head

- Bloaters (Years 1+): Massive fungal growths, throw spore bombs

- Shamblers (Years 5+): Release acidic spore clouds

- Rat King (Decades): Multiple infected fused together into single organism

- Headcrab Zombies (Half-Life): Alien parasites that attach to heads, controlling the body below. Victims remain conscious inside, screaming in reversed audio. Pure nightmare fuel for body horror fans.

Progressive Stages Create Variety

Fungal/parasitic infections excel at creating distinct enemy types from a single infection source. Early stages can be fast and human-like; later stages become monstrous. This progression gives players/readers multiple threat levels and creates tragic "he's too far gone" moments.

Supernatural/Magical

The original zombie origin—no science required, no cure possible. These zombies operate on different rules entirely, making them unpredictable and allowing for creative freedom.

- Voodoo Zombies: The original type from Haitian folklore. Created by bokors (sorcerers) using tetrodotoxin and other toxins to simulate death, then revive victims as mindless servants. Based on real practices, though Hollywood sensationalized them.

- Demonic Possession: Evil Dead's Deadites and REC series demons. Not really "dead" but possessed by malevolent entities. Can speak, taunt, and use strategy. Often unkillable by normal means—requires exorcism, holy items, or destruction of the demon source.

- Cursed/Dark Magic: Reanimation through necromancy or ancient curses. Often tied to specific locations (ancient burial grounds, cursed artifacts). Breaking the curse may end the outbreak.

Cultural Sensitivity with Voodoo

Vodou is a real, practiced religion. If using voodoo zombies, research respectfully and avoid racist stereotypes. Consider whether your story truly needs this specific element or if a fictional magic system might work better.

Radiation-Induced

Born from Cold War atomic fears, radiation zombies tap into anxieties about nuclear weapons, power plants, and scientific experimentation gone wrong.

- Night of the Living Dead: Hints at Venus probe bringing back radiation. Never explicitly confirmed, which makes it creepier. Radiation as mysterious catalyst for unexplained resurrection.

- Fallout Ghouls: Not zombies per se, but radiation-induced mutation that preserves consciousness in some victims while creating feral, mindless monsters in others. The split between intelligent and feral ghouls creates interesting moral questions.

- Atomic Mutation: Classic 1950s B-movie territory. Radiation doesn't just kill—it transforms, mutates, and resurrects. Often paired with giant insects and other atomic monsters.

Cold War Radiation Paranoia

The 1950s-60s saw nuclear testing, duck-and-cover drills, and genuine fear of radioactive fallout. Films used radiation zombies to process societal anxiety about invisible, unstoppable contamination. Modern radiation zombies carry different weight post-Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Chemical/Toxic

Manmade chemical accidents, bioweapons, or toxic spills create zombies. Often involves corporate or military cover-ups and environmental disaster themes.

- Nazi Zombies (COD: Zombies): Element 115 experimentation. Secret Nazi research into super-soldiers creates undead army. Combines WWII aesthetics with conspiracy theories and occult elements.

- Umbrella Corporation (Resident Evil): T-Virus started as bioweapon research. Corporate greed and military applications lead to catastrophic outbreak. Perfect for stories about capitalism, bioethics, and unchecked research.

- "Accident at the Lab" Trope: Classic zombie origin. Experimental chemical breaks containment, infects workers, spreads to nearby town. Simple, effective, and allows focus on survival rather than origin mystery.

Corporate Villains Add Depth

Chemical zombie origins often work best when paired with human antagonists—the corporation trying to contain the outbreak to protect profits, military trying to weaponize it, or government covering it up. This gives your survivors enemies beyond just zombies.

Unknown/Cosmic Origin

No explanation given. The dead simply rise. This approach prioritizes survival horror over scientific investigation and makes the outbreak feel more inevitable and unstoppable.

- The Walking Dead: Origin never explained. Everyone is infected; death triggers reanimation. Removes any hope of finding patient zero or creating a cure. Forces focus onto survival and human conflict.

- Romero's Dead Series: "When there's no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth." Poetic, vague, unstoppable. Could be divine punishment, cosmic alignment, or nothing at all. The mystery is the point.

- Cosmic Horror: Lovecraftian influence—zombies as manifestation of incomprehensible cosmic forces. Humanity is insignificant; the outbreak is beyond our understanding. Creates existential dread.

The Power of Mystery

Unknown origins prevent your story from becoming about "finding the cure" and keep focus on human drama. No scientists to save the day, no government lab to raid. Just survival. However, some readers find this frustrating—gauge your audience.

By Behavior

How zombies act determines your story's pace and the types of challenges survivors face. Behavior categories often matter more to gameplay/survival than origin.

Mindless Feeders

Pure instinct. No strategy, no learning, just hunger. Move toward noise and prey. Can be tricked with simple distractions. Classic Romero style—relentless but predictable.

Best for: Stories about resource management and long-term survival. The threat is attrition, not intelligence.

Pack Hunters

Coordinate attacks without communication. Flank, surround, and overwhelm prey through instinctive cooperation. More dangerous than the sum of their parts.

Best for: Action-oriented stories with tactical challenges. Survivors must outsmart emergent group behavior.

Semi-Conscious

Retain fragments of memory—return to familiar locations, show flickers of recognition when seeing loved ones. Still hostile but tragically human.

Best for: Emotional horror. The "he's still in there" moments. Forces survivors to kill people they knew.

Evolving Intelligence

Land of the Dead zombies learn to use tools, weapons, and basic problem-solving. Big Daddy leads zombies in organized attack using weapons. Terrifying implication: they're adapting.

Best for: Long-term apocalypse stories where zombies become the dominant species, evolving to reclaim the world.

By Physical State

The body's condition affects what your zombies can do and how horrifying they appear. Physical state also determines how long your outbreak can last.

Fresh/Recently Deceased

Death occurred hours or days ago. Body largely intact, organs still present, fluids not yet drained. Often the fastest and most dangerous zombies because muscles and tendons haven't degraded.

Characteristics: Near-human appearance from distance, capable of running (if your zombies run), can potentially pass for living in dim light, still have functional eyes and ears.

Story implications: Creates paranoia—is that person alive or undead? Allows for surprise attacks. Fresh zombies of loved ones are most emotionally impactful.

Decayed/Rotting

Weeks to months deceased. Classic zombie appearance: exposed muscle, hanging skin, visible bones, missing chunks. Slower as tendons weaken but still dangerous in numbers.

Characteristics: Grotesque appearance, foul smell announces presence, vulnerable to being torn apart, may lose fingers/hands making grabs less effective, eyes clouding or missing affects vision.

Story implications: These are the "horde" zombies—shambling masses that overwhelm through numbers. Smell can alert survivors but also means zombies can't sneak up. Easier to destroy individually but dangerous en masse.

Skeletal

Months to years deceased. Mostly bone with scraps of dried tissue. Logically shouldn't function (no muscles to move bones) but horror doesn't always need logic.

Characteristics: Extremely fragile, light enough to be knocked over easily, but also immune to pain and bleeding out. Purely supernatural at this point—muscles can't work without tissue.

Examples: "Bonies" from Warm Bodies—skeletal zombies that have given up all humanity. More animalistic and feral than fresh infected.

Story implications: Represents the "final stage" of infection. No going back, no humanity left. Often used as a ticking clock—infection will eventually reduce all zombies to this state.

Living Infected

Not actually dead—still breathing, heart beating, but infected with rage/disease that makes them zombie-like. Technically not undead, but functionally the same threat.

Characteristics: Can run, maintain full strength, need food/water/sleep, die from injuries like humans, no supernatural durability. May starve after weeks if unable to feed.

Examples: 28 Days Later Rage victims, The Crazies infected, REC early-stage possessed.

Story implications: More "realistic" and potentially curable. Creates moral dilemma—they're still alive under the infection. Killing them is murder, not just destroying a corpse. Also means they have weaknesses: need to breathe (can be drowned/choked), can die from blood loss, won't survive long-term without care.

Mix and Match Categories

You don't need to choose just one category. The most interesting zombie fiction combines multiple types: viral origin that creates both slow shamblers and fast runners, or an infection that starts with living infected who later die and reanimate as mindless corpses. Variety creates more tactical challenges for survivors and keeps your audience guessing.

Undead Folklore Beyond the West

The Western zombie is only one thread in a rich tapestry of global undead folklore. These international revenants offer writers fresh mechanics, cultural depth, and innovative narrative possibilities. Click each creature to explore their unique characteristics and writing applications.

Aswang/Manananggal

Aswang/Manananggal

Origin: Filipino folklore

A horrifying shapeshifter whose upper torso detaches at night, sprouting bat-like wings to hunt. The creature targets pregnant women, using an elongated proboscis tongue to feed on unborn children. What makes it truly terrifying: the distinctive "tik-tik" sound it makes grows FAINTER as it approaches—a cruel deception that inverts our survival instincts.

Writing Applications

- Deceptive Sound Mechanics: The quieter it gets, the closer the danger—creates paranoid tension as characters second-guess their senses

- Find-the-Body Time Pressure: Players/characters must locate and salt the lower half before dawn to trap the creature

- Doppelganger Paranoia: Any pregnant woman could be the Aswang's next victim—or the Aswang itself in disguise

- Vulnerabilities Create Puzzles: Salt, garlic, stingray tail whips—regional defenses add cultural authenticity

- Dual Threat Model: Different dangers during day (discovery risk) vs. night (active hunting)

Phi Krasue

Phi Krasue

Origin: Thai folklore (also found in Lao, Cambodian, and Malaysian traditions as Krasue, Ahp, or Penanggalan)

A cursed woman whose head detaches from her body each night, trailing glowing entrails as it floats through the darkness. By day, she appears completely normal—a neighbor, a friend, perhaps even family. She must return to her body before dawn or die, creating a vulnerability that can be exploited by those brave enough to find and salt the body's neck stump.

Writing Applications

- Hidden Monster Trope: The creature lives among your characters—creates trust issues and detective elements

- Sympathetic Monster: Often portrayed as cursed rather than evil—moral complexity in whether to kill or cure

- Body-Guarding Gameplay: Find and protect/destroy the vulnerable body while the head hunts

- Visual Horror: The glowing entrails create a distinctive, trackable enemy—visceral and memorable

- Cultural Variants: Different Southeast Asian versions offer slight mechanic variations (Penanggalan uses vinegar to shrink organs)

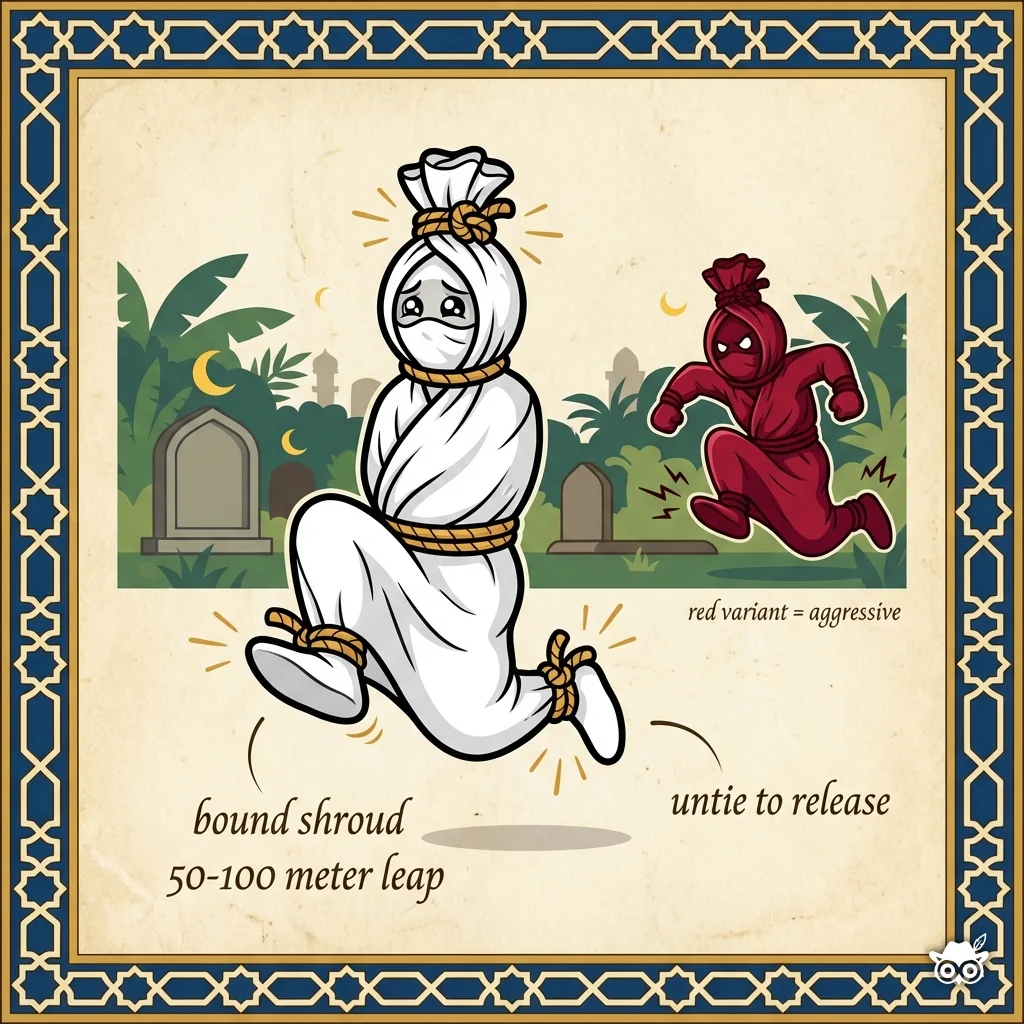

Pocong

Pocong (Shroud Ghost)

Origin: Indonesian/Malaysian Islamic folklore

When a Muslim burial is performed incorrectly—specifically when the shroud's binding knots are not untied after 40 days—the deceased becomes trapped in their burial cloth. Unable to walk, the Pocong moves by hopping, yet can leap 50-100 meters in a single bound. Unlike malevolent undead, most Pocong simply seek release from their shroud prison. However, the rare Red Pocong is violently aggressive, making for a terrifying boss-level threat.

Writing Applications

- Non-Hostile Undead: Creates moral choices—help them or flee? Not all encounters need to be combat

- Unpredictable Movement: The hop-then-mega-leap pattern makes them hard to track and escape from

- Religious Horror: Grounds terror in cultural burial practices—adds authenticity and depth

- Boss Variant System: Red Pocong as rare, aggressive version creates escalating threat hierarchy

- Quest Objectives: "Free the trapped soul" missions offer alternatives to kill-everything gameplay

- Cultural Respect Required: Players/characters must learn Islamic burial rituals to solve encounters properly

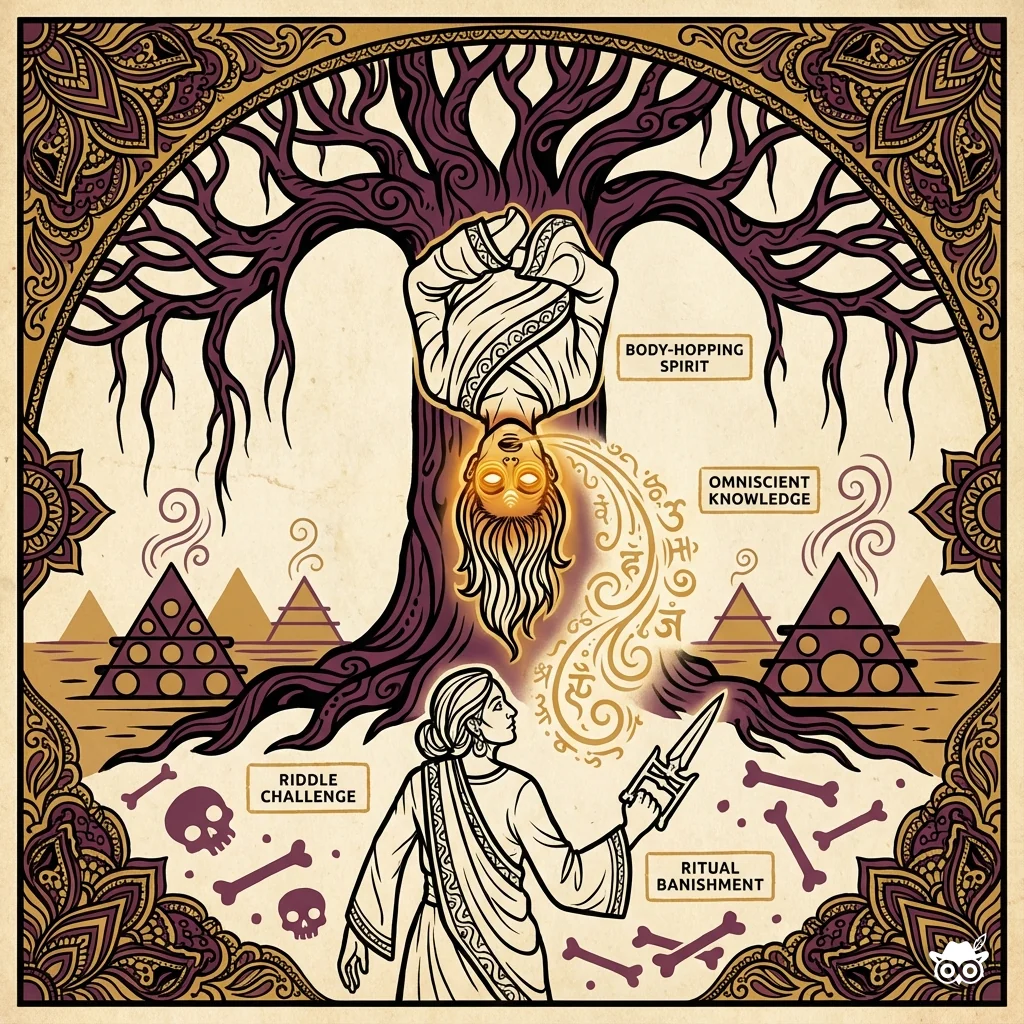

Vetala

Vetala (The Riddler)

Origin: Indian folklore, especially the Vetala Panchavimshati (25 Tales of the Vampire)

Not a reanimated corpse but a demonic entity that possesses and reanimates dead bodies as vessels. The Vetala can enter and exit corpses at will, making it impossible to destroy by harming the host. More terrifying yet: it possesses omniscient knowledge of past, present, and future. In classic tales, the Vetala poses riddles to its captors—answer correctly and it escapes to possess another body; answer incorrectly and die.

Writing Applications

- Impossible to Kill Physically: Destroying the body is meaningless—must use magic/ritual to banish the spirit itself

- Body-Hopping Enemy: Creates paranoia as the Vetala can possess any corpse (or living person in some variants)

- Riddle Challenges: Integrates puzzle-solving into horror—intellectual threat alongside physical danger

- Dual Role Design: Can be both antagonist AND source of crucial information (if you can outwit it)

- Knowledge as Power: Its omniscience lets it manipulate characters with their secrets and futures

- Cultural Depth: Draw from the 25 classic tales for pre-written riddle scenarios and moral dilemmas

Slavic Upyr

Slavic Upyr (Upir/Vampire)

Origin: Eastern European folklore, pre-dating Bram Stoker's Dracula

The original vampire—far removed from the elegant aristocrat of Victorian fiction. The Upyr is a bloated, grotesque revenant that walks in DAYLIGHT, feeding on both blood and life force itself. Unlike later romanticized vampires, it prioritizes hunting its own family members first. Archaeological evidence from Slavic burial sites shows real stakes and ritual dismemberment, proving our ancestors took this threat seriously.

Writing Applications

- No Daylight Safety: Removes the classic vampire refuge—creates constant threat level

- Family as Victims: Personal stakes (no pun intended)—the undead father/mother hunting their children

- Grotesque Over Glamorous: Emphasizes decay and horror over seduction—pure monster design

- Life Drain Mechanic: Victims don't just lose blood but vitality itself—slow, draining death rather than instant

- Archaeological Authenticity: Real historical burial practices add credibility—research Slavic vampire graves for details

- Required Ritual: Staking alone isn't enough—must also behead and burn to prevent return

The Science of Zombies

The best zombie fiction grounds its horror in plausible science. Understanding real parasites, diseases, and epidemiology helps you create infections that feel terrifyingly possible.

Real-World "Zombie" Parasites

Nature has already created zombie-making organisms. The fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis infects ants, hijacking their behavior to spread its spores. But here's the fascinating detail that makes it even creepier: Penn State research revealed the fungus doesn't invade the ant's brain at all. Instead, fungal cells form a three-dimensional network surrounding muscle fibers throughout the body, controlling it "like a puppeteer pulls strings."

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis (Zombie Ant Fungus)

Infected ants climb to precisely 25cm above the forest floor, bite into leaf veins, and die as the fungus erupts from their heads. The fungus has evolved with ants for 45+ million years, perfecting its mind control without ever touching the brain.

Fiction Inspiration: A pathogen that controls victims through peripheral nervous system manipulation, bypassing brain defenses entirely. Victims remain conscious but unable to control their actions.

Toxoplasma gondii (Cat Parasite)

This parasite makes infected rodents lose their fear of cats—even developing attraction to cat urine. An estimated 30% of humans are infected, with subtle personality effects including increased risk-taking and delayed reaction times.

Fiction Inspiration: A parasite that subtly rewrites fear responses, making victims attracted to danger rather than fleeing from it. The infected seek out threats.

Ampulex compressa (Emerald Jewel Wasp)

This wasp delivers two precise neurotoxic stings to a cockroach: the first paralyzes the front legs temporarily, the second injects venom directly into the brain's decision-making center. The roach can walk but has no will to escape. The wasp then leads it "like a dog on a leash" by its antenna to a burrow, where it lays an egg. The cockroach remains alive and aware while wasp larvae eat it from the inside out over eight days.

Fiction Inspiration: A two-stage infection: first immobilization, then complete behavioral override. Victims are fully aware but docile, following commands without resistance. Perfect for stories exploring loss of agency.

Dicrocoelium dendriticum (Lancet Liver Fluke)

This parasite's lifecycle requires it to get from an ant into a grazing animal. One larva—a "sacrificial zombie-maker"—migrates to the ant's brain while hundreds of others hide in the abdomen. The brain larva sacrifices any chance of reproduction to control the ant, forcing it to climb to the top of a grass blade at dawn and dusk, clamp its jaws, and wait to be eaten. If not eaten, the ant returns to normal during the day, only to be controlled again at feeding times.

Fiction Inspiration: Infection with divergent roles—some infected become mindless controllers while others remain hidden cargo. The sacrifice of the brain-controlling parasite adds tragic complexity: not all infected serve the same purpose.

Paragordius tricuspidatus (Hairworm)

This parasitic worm needs water to reproduce but lives inside terrestrial crickets. When mature, it releases proteins that hijack the cricket's central nervous system, driving it to seek water. Studies show 81.5% of infected crickets successfully "commit suicide" by jumping into water, where the worm—often longer than the cricket itself—erupts from the body to complete its lifecycle. The precision of this behavior modification is chilling: infected crickets show no interest in water until the exact moment the parasite is ready, then become irresistibly drawn to it.

Fiction Inspiration: Time-delayed behavioral programming with near-perfect success rates. Victims appear normal until a trigger moment when they're compelled toward a specific, lethal action. The high suicide success rate suggests terrifyingly effective neurological manipulation.

Epidemiology for Writers

The R₀ (basic reproduction number) tells you how contagious a disease is—how many people one infected person typically infects. Understanding this helps you write realistic outbreak scenarios.

| Disease | R₀ | What This Means |

|---|---|---|

| Measles | 12-18 | Most contagious known disease |

| COVID-19 (BA.2) | ~12-22 | Extremely transmissible variants |

| 1918 Flu | 1.4-2.8 | Killed 50 million despite "low" R₀ |

| Ebola | 1.5-2.5 | Contact transmission limits spread |

| Fictional Zombie Virus | 5-15 | Would require 80-93% immunity to stop |

Collapse Timeline

Societal breakdown happens faster than you might think. Within 24 hours: confusion and scattered reports. Days 1-3: hospitals strain, panic buying. Week 2: supply chains break. Month 2+: complete collapse in affected areas. The 2003 Northeast Blackout went from first failure to 50 million without power in just 3 minutes.

Rabies and Prion Diseases: Real-World Inspiration

Some of the most terrifying zombie characteristics come directly from real diseases that already exist. These aren't just inspiration—they're proof that nature can be more horrifying than fiction.

Rabies: The Original Zombie Virus

Rabies is the closest thing we have to a real zombie infection. Once symptoms appear, it's nearly 100% fatal. The virus spreads through bites, traveling along peripheral nerves to reach the brain—a journey that can take weeks or months, creating a hidden incubation period.

Classic Zombie Traits Inspired by Rabies:

- Hyperactivity and aggression: Infected animals become abnormally active and violent

- Compulsive biting: The virus concentrates in saliva and drives the host to bite

- Hydrophobia: Painful throat spasms when trying to swallow water

- Hypersalivation: The infamous "foaming at the mouth"

- Hallucinations and delirium: Victims lose touch with reality

Fiction Inspiration: Danny Boyle's 28 Days Later explicitly based its "Rage" virus on a modified rabies infection. The film's 28-day incubation period, aggressive behavior, and bite transmission are all rabies characteristics amplified to horrifying extremes.

Prion Diseases: The Unstoppable Infection

Prions aren't bacteria or viruses—they're misfolded proteins that convert healthy proteins into more prions. They contain no genetic material, making them impossible to kill with heat, radiation, or disinfectants. They create spongiform (sponge-like) damage in the brain, and are 100% fatal with no treatment or cure.

Types of Prion Diseases:

- Kuru ("The Laughing Death"): Discovered in the Fore tribe of Papua New Guinea, transmitted through ritualistic cannibalism of deceased relatives. Victims developed uncontrollable laughter and tremors before death. The epidemic ended when cannibalism stopped, but demonstrates human-to-human transmission through consumption of infected tissue.

- Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD): Occurs randomly in about 1 in 1 million people. Rapid dementia, muscle stiffness, confusion. Death typically within months of first symptoms.

- Variant CJD (Mad Cow Disease): Transmitted from eating infected cattle. The 1990s UK epidemic killed over 170 people and led to the slaughter of millions of cattle.

- Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD): Affecting deer and elk across North America, earning it the nickname "zombie deer disease." Infected animals display weight loss, stumbling, lack of fear, aggression, and excessive salivation. It spreads through environmental contamination and remains in soil for years.

Fiction Inspiration: A disease that can't be killed, spreads through environmental contamination, and remains infectious indefinitely. Perfect for post-apocalyptic settings where simply avoiding the infected isn't enough—the environment itself is contaminated.

When the CDC Used Zombies

On May 16, 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention did something unprecedented: they used zombies to teach Americans about emergency preparedness. Dr. Ali S. Khan, director of the CDC's Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, published a blog post titled "Preparedness 101: Zombie Apocalypse." It would become one of the most successful public health campaigns in history.

The genius was in the approach. Khan recognized that disaster preparedness messages were boring—people ignored them. But zombies? People loved zombies. The post walked readers through what supplies to gather (water, food, medications, tools, sanitation items) and what plans to make (evacuation routes, emergency contacts, emergency meeting location) using a zombie apocalypse as the hook.

The Core Message

"If you are generally well equipped to deal with a zombie apocalypse you will be prepared for a hurricane, pandemic, earthquake, or terrorist attack." —Dr. Ali S. Khan

This single insight transformed boring preparedness advice into viral content. The same emergency kit works for any disaster. The same family communication plan helps whether you're facing floods or fictional undead.

The Results Were Staggering:

- The campaign cost approximately $87 (for the stock zombie photo) plus staff time

- Normal CDC blog posts received about 3,000 hits over several weeks

- The zombie post got 30,000 hits the first evening—and crashed the CDC's servers

- In October 2011, the CDC released a graphic novel, "Preparedness 101: Zombie Pandemic," which received 517,600+ views

- The campaign generated international media coverage and made preparedness cool

The CDC's zombie campaign proved that fiction—even absurd fiction—can serve real-world purposes. By meeting people where their interests already were (zombie media was experiencing a massive boom in 2011), the CDC delivered genuinely useful information that might save lives during real emergencies.

For writers, this demonstrates the cultural power of zombie fiction. Your stories aren't just entertainment—they're part of a larger conversation about survival, society, and how we respond to crisis. The line between fiction and practical preparation is thinner than you might think.

Zombie Media Deep Dive

The best way to learn zombie writing is to study the masters across every medium. Each format—books, comics, games—has unique strengths that can inform your interactive fiction. Books excel at internal character work, comics pioneer visual horror language, and games innovate mechanics that can translate to choice-based storytelling.

Essential Books

These novels demonstrate the range of what zombie fiction can achieve, from military procedurals to literary fiction to scientific horror.

-

Max Brooks - The Zombie Survival Guide (2003) and World War Z (2006)

Brooks revolutionized zombie fiction with a mock survival manual followed by an oral history of a global zombie war. World War Z was directly inspired by Studs Terkel's oral histories, structuring the narrative as post-war interviews. The fragmented perspective allows Brooks to examine zombie apocalypse from military, political, economic, and personal angles. Writing lesson: Multiple viewpoints can create a fuller picture than any single protagonist could provide. -

Brian Keene - The Rising (2003)

Winner of the Bram Stoker Award, Keene's zombies are possessed by demons rather than driven by virus or radiation. They retain intelligence, memories, and can use weapons and drive cars. This creates a fundamentally different threat dynamic. Writing lesson: Intelligent zombies open tactical storytelling—they can set traps, coordinate attacks, and learn from failures. -

Mira Grant - Feed (Newsflesh Series, 2010)

Set 26 years after the initial outbreak, Grant's world has adapted to a zombie reality with amplification testing and security protocols. The series follows blog journalists covering a presidential campaign. Hugo Award finalist that demonstrates how society might genuinely adapt. Writing lesson: Post-apocalypse doesn't mean civilization ends—it means civilization changes. -

Colson Whitehead - Zone One (2011)

Literary zombie fiction that explores trauma and capitalism through the lens of post-apocalyptic Manhattan cleanup crews. Whitehead introduces "stragglers"—zombies frozen in mundane activities like stocking shelves or typing at keyboards, caught between death and purpose. Writing lesson: Zombie behavior can reflect thematic concerns; stragglers embody workers trapped in meaningless labor. -

M.R. Carey - The Girl with All the Gifts (2014)

Infected children retain intelligence and self-awareness, creating profound ethical questions. The fungal "Ophiocordyceps" basis grounds the horror in science while allowing for unique variations. Writing lesson: Smart infected characters can be protagonists, not just threats, opening entirely new narrative territory. -

Isaac Marion - Warm Bodies (2010)

Proved zombie romance could work by giving readers a sympathetic zombie POV character who maintains his internal monologue. R's perspective makes the familiar genre fresh while exploring consciousness and connection. Writing lesson: POV choice transforms genre expectations—seeing through undead eyes changes everything.

Study Across Subgenres

Don't just read action-focused zombie thrillers. Military procedurals teach pacing, literary fiction teaches character depth, YA teaches accessibility, and horror teaches tension. Each subgenre has techniques you can adapt to interactive fiction.

Comics & Graphic Novels

Comics have pioneered zombie storytelling techniques that translate surprisingly well to text-based fiction, particularly in visual pacing and reveal mechanics.

| Comic Series | Key Innovation | Writing Applications |

|---|---|---|

| The Walking Dead (2003-2019) | 193 issues in black and white. Kirkman allegedly claimed the series would reveal an alien invasion origin to get Image Comics to publish it, then proceeded to write it for 16 years without ever addressing that supposed plot point. | Demonstrates sustainable long-form narrative. Black and white aesthetic proves gore doesn't need color to impact. Learn: Focus on character arcs over spectacle for longevity. |

| Marvel Zombies (2005+) | Superpowered zombies retain their abilities but lose their morality. A zombified Spider-Man can still web-swing while hunting human prey. | Familiar characters made horrifying creates instant reader investment. Learn: Subverting reader expectations of known entities generates fresh tension. |

| DCeased (2019-2023) | Darkseid's corrupted Anti-Life Equation transmitted through screens creates the "Anti-Living." Tech-based transmission is devastatingly fast in DC's modern world. | Transmission method shapes outbreak pace and story structure. Learn: How zombies spread determines your narrative timeline and isolation mechanics. |

| iZombie (2010-2012) | Protagonist must eat one brain per month or lose intelligence. Each brain consumed grants temporary memories and personality traits of the deceased. | Creates episodic structure while maintaining arc. Mystery + zombie procedural hybrid. Learn: Unique zombie rules can generate ongoing plot engines. |

What Comics Teach Writers

- Panel-to-panel reveals: Comics excel at page-turn reveals. Translate this to scene-to-scene or choice-to-consequence pacing.

- Visual shorthand: A single panel can convey disaster scope. In text, learn to do heavy lifting with a single well-chosen detail.

- Cliffhanger structure: Issue-ending hooks keep readers coming back. CYOA nodes should echo this tension preservation.

- Silent horror: Panels without dialogue can be terrifying. Try passages of pure action/description without character commentary.

Video Games

Video games have pioneered zombie mechanics that interactive fiction can adapt. While you can't replicate gameplay, you can translate the design principles behind these systems.

-

Left 4 Dead (2008-2009) - AI Director System

The game's revolutionary AI Director monitors player stress levels, performance, and positioning to dynamically spawn enemies. When players are calm, it escalates. When overwhelmed, it provides breathing room. This created emergent pacing that felt authored but remained unpredictable.

Interactive Fiction Application: Variable pacing based on reader choices. Track "stress" through failed choices or resource depletion. When readers have succeeded recently, introduce harder challenges. After failures, provide easier wins or character moments. The Director also introduced Special Infected—unique zombie types (Tanks, Witches, Hunters) that require specific tactics.

Adaptive Storytelling: Your branching narrative can acknowledge player patterns. If readers consistently choose stealth, introduce an encounter where stealth fails. If they always fight, present a scenario where combat is futile. -

Dead Rising (2006+) - Improvised Weapons & Time Pressure

Features 140+ improvised weapons from a shopping mall setting, from teddy bears to lawnmowers. The combo weapon crafting system (duct tape + creativity = new tools) rewards experimentation. The original game ran on a strict 72-hour real-time timer—if you didn't complete objectives, survivors died permanently.

Interactive Fiction Application: Resource creativity over resource scarcity. Give readers environmental assets they can combine. "You have duct tape and a baseball bat" becomes meaningful if readers can suggest combinations. The timer creates urgency—time-limited choices or survival countdowns generate similar pressure without real-time mechanics.

Environmental Storytelling: Dead Rising's mall is packed with environmental comedy and tragedy. Your locations should be similarly rich with interactive details that reward exploration choices. -

Dying Light (2015) - Day/Night Cycle with Volatiles

First-person parkour zombie survival where movement is as important as combat. During the day, zombies are slow and manageable. At night, "Volatiles"—fast, intelligent hunters—emerge, transforming the game into survival horror. This creates natural risk/reward cycles: venture out at night for better supplies but face exponentially greater danger.

Interactive Fiction Application: Time-of-day choices with dramatically different consequences. Scavenging at night yields better resources but higher risk. Day trips are safer but more crowded (other survivors are also out). Players must weigh when to move.

Movement as Mechanic: Dying Light proves traversal can be engaging. In text, this becomes route choice—rooftops vs. streets vs. sewers. Each path has unique hazards and opportunities. Parkour-style decision trees where players navigate obstacle courses through choice.

Games Mechanics ≠ Direct Translation

Don't try to replicate game mechanics literally (health bars, XP systems, inventories with item limits). Instead, extract the feeling those mechanics create. Left 4 Dead's Director creates dynamic pacing—your choice structure can achieve similar variety. Dead Rising's timer creates urgency—your narrative can create urgency through consequences, not countdown clocks. Focus on the emotional and strategic experience, not the mechanical implementation.

What Games Teach: Player Agency

Games excel at making players feel their choices matter. Even when paths converge, the experience of having chosen feels meaningful. Your CYOA should provide:

- Meaningful constraints: Limited resources force prioritization

- Visible consequences: Choices change what's available later

- Risk assessment: Players weigh probability vs. payoff

- Personal expression: Choices reflect play style

What Games Struggle With: Depth

Games often sacrifice narrative depth for mechanical variety. Interactive fiction can reverse this—leverage text's strengths:

- Internal monologue: Show fear, doubt, regret in real-time

- Moral complexity: Choices with no right answer, only trade-offs

- Relationship nuance: Character bonds that shift gradually

- Thematic resonance: Horror that explores ideas, not just threats

Cross-Medium Story Design Exercise

Pick one element from each medium: A character dynamic from a book, a visual motif from a comic, and a game mechanic. Now design a CYOA scenario that combines all three. For example: Brooks' oral history structure (book) + Marvel Zombies' corrupted heroes (comics) + Dead Rising's improvised weapons (games) = A fragmented narrative where survivors tell their stories of fighting zombified first responders using whatever they could grab from emergency vehicles.

Genre Variations & Meaning

Zombies are remarkably versatile narrative tools. They can terrify, amuse, move us emotionally, or provoke deep thought—depending on how you frame them. Understanding genre approaches and metaphorical layers helps you make intentional storytelling choices.

Genre Approaches

Click each genre to explore how different approaches transform the same undead monster into entirely different storytelling experiences.

Horror

Horror

The classic approach. Zombies as instruments of pure terror—visceral, relentless, hopeless. Fear, tension, and gore dominate. Characters exist in constant mortal danger, and endings often trend toward the tragic or bittersweet.

Key Characteristics

- Survival is uncertain: Main characters can and do die

- Visceral descriptions: Don't shy from the gruesome details

- Hopeless atmosphere: Even victories feel temporary

- Moral decay: Survivors become as dangerous as zombies

Examples

28 Days Later (2002), The Walking Dead (2010-2022), REC (2007), Train to Busan (2016)

Zombie Comedy

Zombie Comedy (Zom-Com)

Blending horror and humor creates subversive, self-aware narratives. Characters often know zombie movie tropes and comment on them. The absurdity of the apocalypse becomes the joke. "Rule #1: Cardio."

Key Characteristics

- Meta-awareness: Characters reference zombie movie conventions

- Mundane meets apocalypse: Everyday problems persist despite zombies

- Creative violence: Kills become comedic set pieces

- Heart beneath laughs: Best zom-coms have emotional cores

Examples

Shaun of the Dead (2004), Zombieland (2009), Return of the Living Dead (1985), One Cut of the Dead (2017)

Zombie Romance

Zombie Romance

Love persists beyond death. These stories often feature sentient or recovering zombies capable of emotion and connection. Romeo & Juliet dynamics arise when love crosses the living/undead divide.

Key Characteristics

- Zombie POV often featured: We see their internal struggle

- Recovery/cure possible: Love becomes catalyst for change

- Forbidden love: Society opposes human/zombie relationships

- Metaphor for transformation: Love changes us fundamentally

Examples

Warm Bodies (2013), Life After Beth (2014), My Boyfriend's Back (1993), iZombie (TV series)

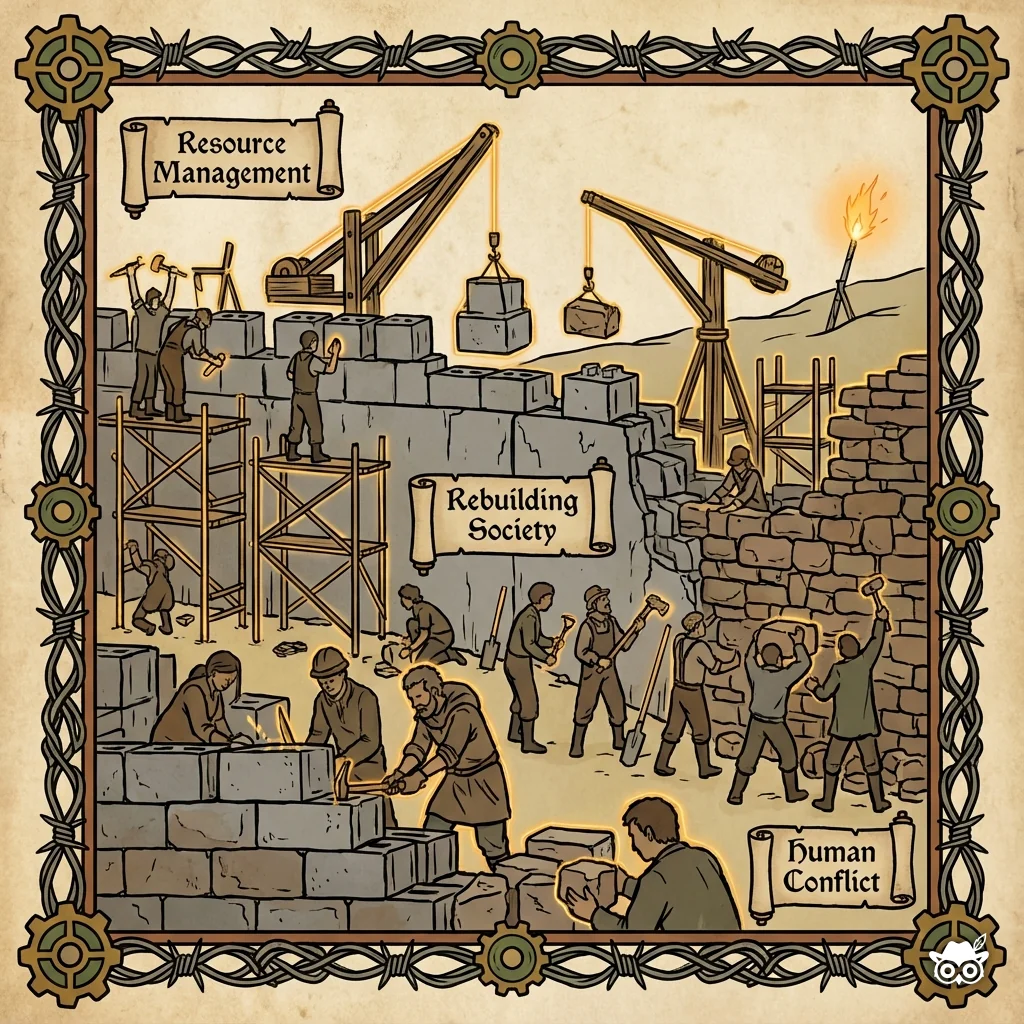

Post-Apocalyptic

Post-Apocalyptic Survival

Zombies fade into background threat as the focus shifts to rebuilding civilization. Stories emphasize resource management, community dynamics, political struggles, and what it means to be human when society has collapsed.

Key Characteristics

- Zombies as environmental hazard: Like weather or wildlife

- Human conflict primary: Rival settlements, power struggles

- Infrastructure matters: Water, power, farming become plot points

- Generational stories: Children who never knew the old world

Examples

The Walking Dead (later seasons), World War Z (rebuilding chapters), Daybreak (TV series), The Last of Us Part II

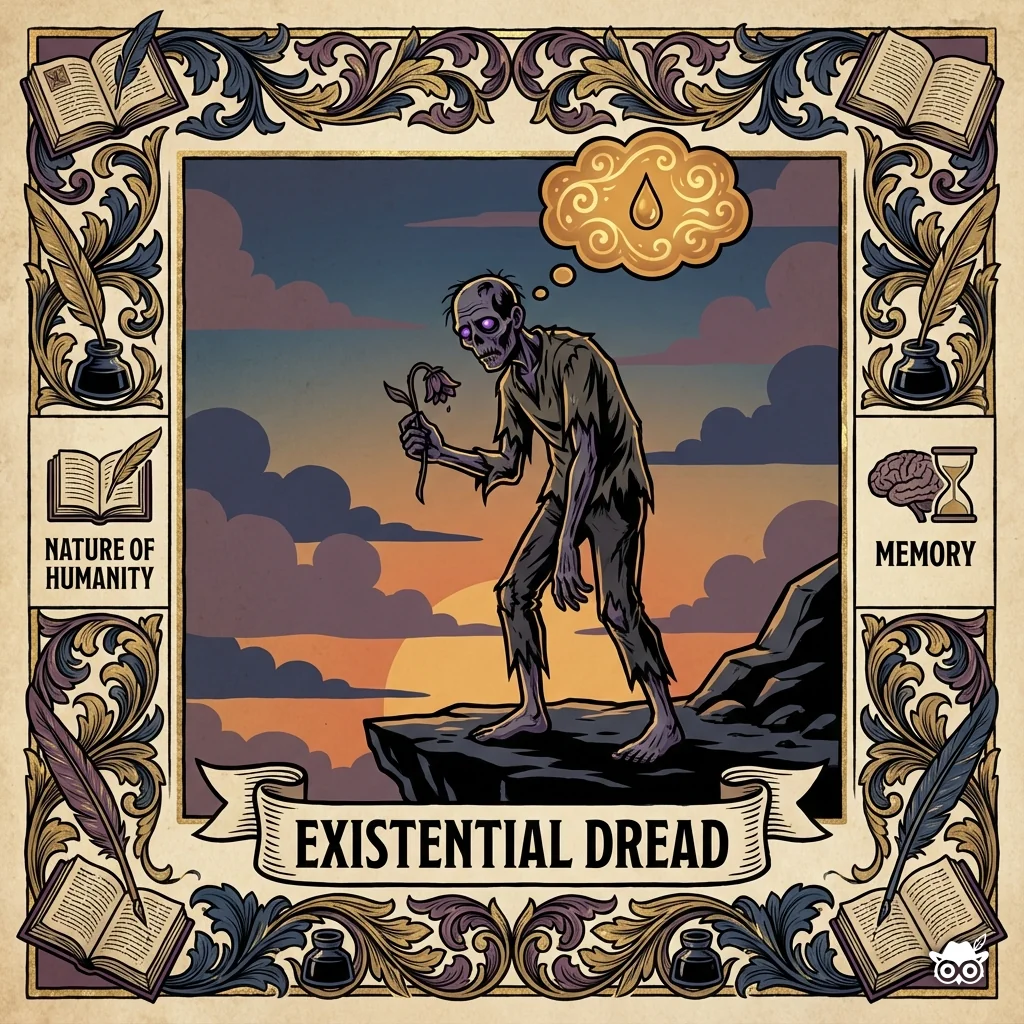

Literary/Philosophical

Literary/Philosophical

Zombies become vehicles for exploring what makes us human. Character-driven narratives with thematic depth, examining consciousness, identity, prejudice, and the nature of humanity itself.

Key Characteristics

- Action serves theme: Every scene explores larger questions

- Complex characterization: No simple heroes or villains

- Ambiguous morality: Right choices aren't always clear

- Literary prose style: Elevated language, introspection

Examples

The Girl With All the Gifts (2014), Zone One by Colson Whitehead (2011), The Reapers Are the Angels (2010)

Children's Media

Children's Media

Zombies reimagined as friendly, misunderstood, or controllable. Often features integration themes, acceptance of differences, and creative explanations for zombie existence that remove horror elements entirely.

Key Characteristics

- Disney's ZOMBIES: Lime soda accident, Z-bands control zombie state, high school integration storyline

- Monster High: Zombies attend school with other monsters, friendship themes

- Plants vs. Zombies: Silly, cartoon zombies in strategic gameplay

- Key themes: Prejudice is wrong, everyone deserves acceptance, differences make us stronger

Examples

Disney's ZOMBIES series (2018-), Monster High, Plants vs. Zombies, Hotel Transylvania franchise

Zombies as Metaphor

Beyond genre, zombies carry metaphorical weight. The shambling horde can represent almost any societal fear or critique. Understanding these layers adds depth to your narrative—even if readers never consciously notice them.

George Romero's Dawn of the Dead (1978) set the outbreak in a shopping mall. Zombies mindlessly wander store to store like brain-dead shoppers. "They're us," a character realizes. The metaphor: modern consumer culture has already made us zombies. This theme appears in countless works, from They Live to Black Friday satire.

Shaun of the Dead's brilliant opening shows the living going through their routines like zombies BEFORE the outbreak even begins—glazed eyes on the morning commute, mindless consumption, robotic interactions. The zombie apocalypse just makes literal what was already happening. Are we already the walking dead, going through motions without truly living?

This metaphor became especially resonant post-COVID. Zombie narratives explore quarantine zones, overwhelmed medical systems, government incompetence, debates over personal freedom vs. public safety, and the question: how do you balance compassion for the infected with protecting yourself? Films like Contagion and 28 Days Later feel uncomfortably prescient.

Romero's Land of the Dead (2005) shows the wealthy living in luxury high-rises while the poor struggle outside the walls. When zombies finally breach the barriers, they function as an uprising against power structures. The metaphor: the masses you've exploited and ignored will eventually rise up. See also: Snowpiercer's class revolt using similar imagery.

Choose Your Metaphorical Angle First

Before writing, ask yourself: What does the zombie outbreak represent in my story? Consumerism? Pandemic? Loss of humanity? Class struggle? Political extremism? Environmental collapse? Once you identify the metaphor, it informs every choice—from outbreak cause to character reactions to your ending. The best zombie fiction works on both literal and metaphorical levels simultaneously.

Surface Level (What Happens)

- Zombies attack a mall

- Survivors defend territory

- Resources run low

- Horde eventually wins

Metaphorical Level (What It Means)

- Temple of consumerism invaded

- Protecting meaningless material goods

- Empty consumption can't sustain us

- We become what we feared

"The metaphor of the zombie is so rich and resonant. You can hang almost any anxiety, any fear, any social critique on it and it works." — Max Brooks, World War Z author

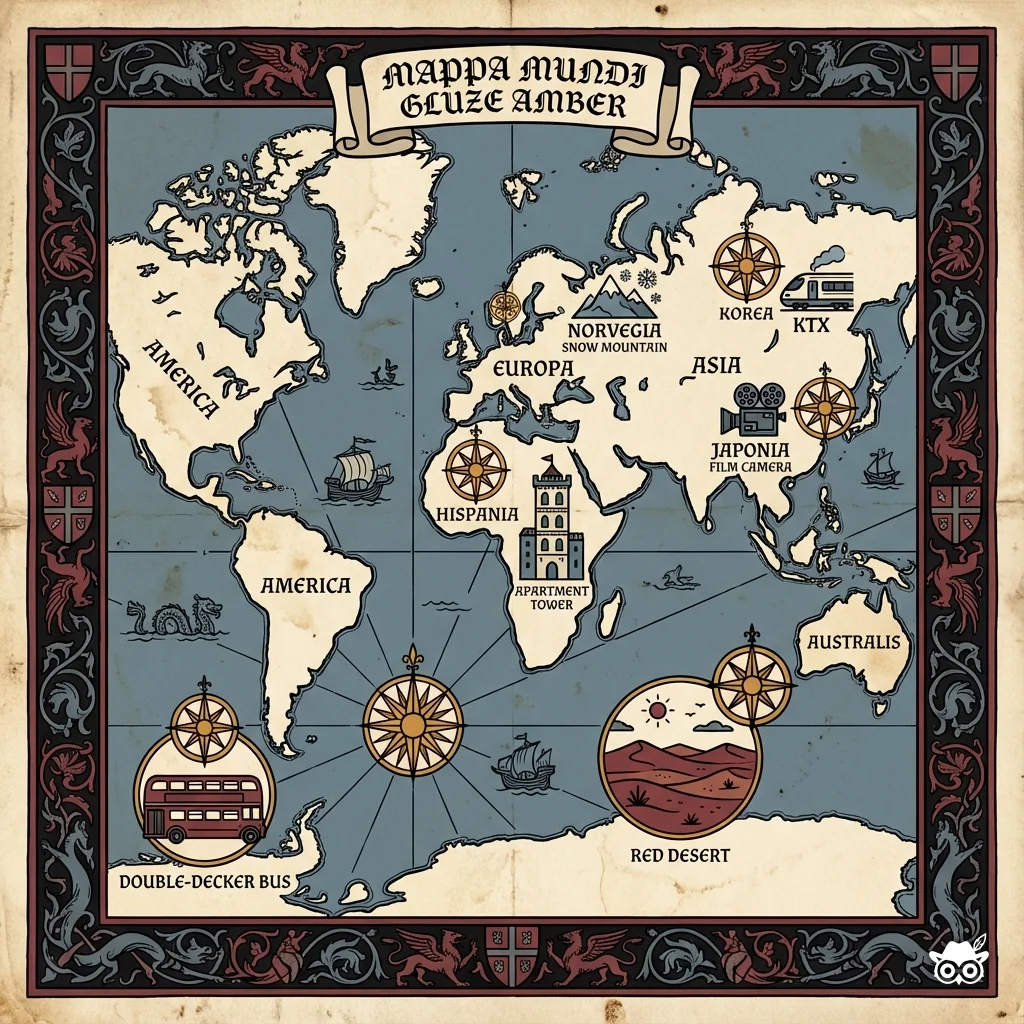

International Zombie Fiction

Different cultures bring unique perspectives to zombie stories, shaped by their own folklore, fears, and cinematic traditions. While Hollywood dominates the genre, some of the most innovative and fresh zombie narratives have emerged from international filmmakers who reimagine the undead through their cultural lenses.

🇰🇷 Korean Zombie Fiction

Train to Busan (2016)

The first major Korean zombie blockbuster set on a KTX high-speed train. A masterclass in confined-space tension and social commentary. 95% Rotten Tomatoes.

Kingdom (2019-2020, Netflix)

A stunning Joseon-era zombie period piece blending political intrigue with undead horror. Proves historical settings can reinvigorate the genre.

All of Us Are Dead (2022)

High school outbreak series that combines teen drama with brutal zombie action. Explores class divides and student-authority power dynamics.

#Alive (2020)

Apartment survival story for the social media generation. Shows how modern technology changes isolation narratives.

🇪🇸 Spanish Zombie Fiction

REC Series (2007-2014)

Found footage horror masterpiece set in a Barcelona apartment building. The twist: it's contagious demonic possession, not a virus. Claustrophobic terror that redefined found footage horror.

🇯🇵 Japanese Zombie Fiction

One Cut of the Dead (2017)

A revolutionary meta-comedy about making a zombie film. Made on a $25,000 budget and grossed $31 million worldwide. Features an ingenious twist structure that transforms on rewatch. Proves you don't need money to innovate.

🇳🇴 Norwegian Zombie Fiction

Dead Snow (2009)

Nazi zombies rising from Norwegian snow. B-movie premise elevated by genuine craftsmanship and dark humor. Shows how specific settings (snow, mountains, isolation) create unique tactical challenges.

🇦🇺 Australian Zombie Fiction

Cargo (2017)

Emotional father-daughter survival story set in the Australian outback. Martin Freeman gives a heartbreaking performance as a man with 48 hours before he turns. More meditation on death and legacy than action thriller.

🇬🇧 British Zombie Fiction

28 Days Later (2002)

Danny Boyle's game-changing fast zombie film shot on digital video. Created the modern "rage virus" infected and influenced a generation of filmmakers.

28 Weeks Later (2007)

Military occupation sequel exploring what happens during attempted reconstruction. Opening sequence is legendary.

Shaun of the Dead (2004)

Edgar Wright's romantic comedy with zombies. Perfect blend of genuine scares and British humor. Proved zombie films don't have to be straight horror.

The Girl with All the Gifts (2016)

Intelligent fungal infected and a child who might be humanity's salvation. Based on the novel by M.R. Carey. Challenges what "salvation" means.

Mine International Cinema for Fresh Ideas

Western zombie fiction has explored certain tropes to exhaustion. International zombie films offer fresh perspectives shaped by different cultural fears, storytelling traditions, and social contexts. Korean films excel at social hierarchy commentary. Japanese films bring unique genre-blending creativity. British films master dark humor and working-class realism. Study how these filmmakers approach familiar scenarios—you'll find approaches and angles that feel new to Western audiences simply because they emerge from different creative traditions.

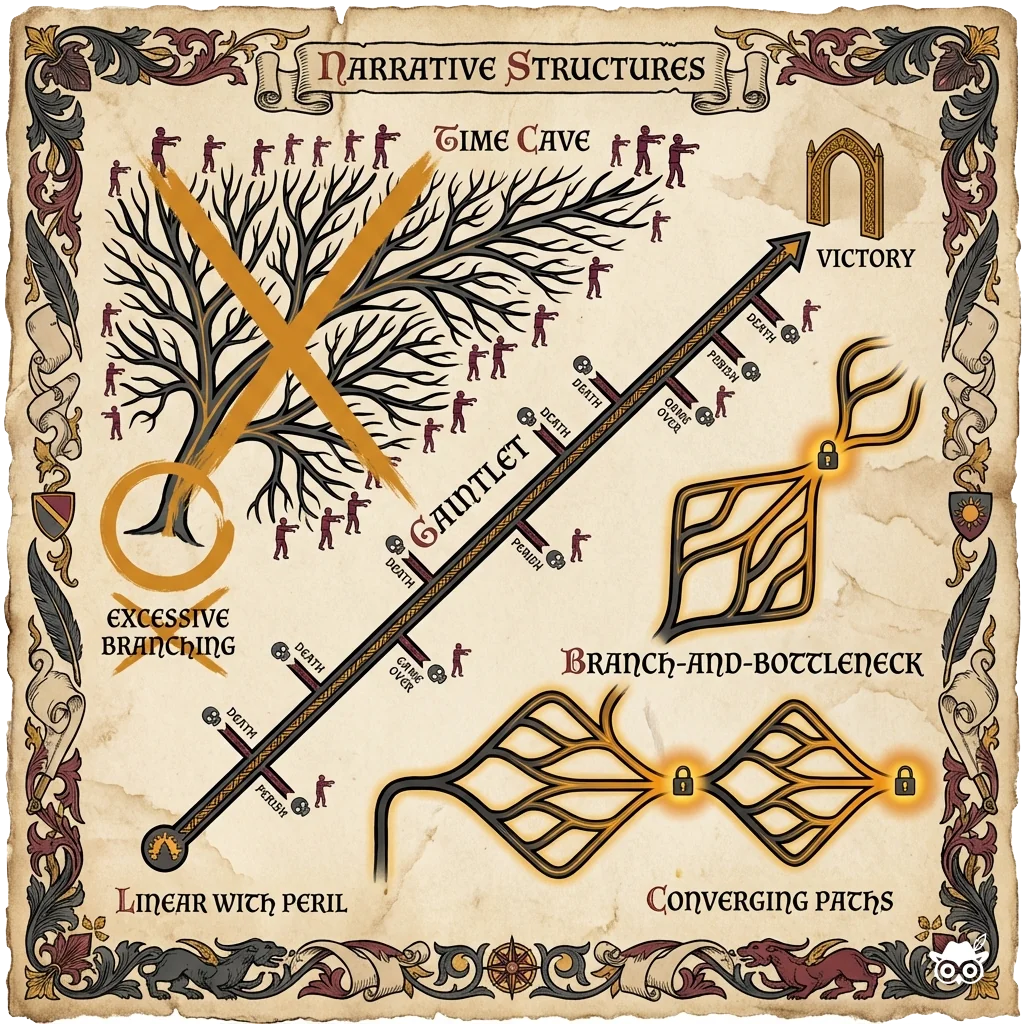

Structuring Your Story

The biggest challenge in choose-your-own-adventure writing isn't creativity—it's architecture. Seven binary choices create 128 possible paths. Twenty choices create over a million. You need strategies to manage this complexity.

The Branch-and-Bottleneck Method

The most sustainable approach for long-form interactive fiction. Branches diverge for meaningful variation, then converge at "bottleneck" points—events that happen regardless of which path the reader took. This lets you maintain scope while preserving the feeling of meaningful choice.

Natural Convergence Points for Zombie Stories

- Location Arrivals: Everyone eventually reaches the safehouse, hospital, or extraction point—how they arrive and in what condition varies.

- Major Events: The horde reaches the barricade. The helicopter arrives. The power fails. These happen to all readers.

- Time Cycles: Dawn breaks. Night falls. The weekly supply run. Time-based events naturally synchronize branches.

- Character Deaths: Key NPCs may die at different times on different paths, but major deaths can serve as convergence points.

The Gauntlet Structure

Perfect for survival horror. A relatively linear central thread where bad choices lead to death, backtracking, or quick rejoining. The zombie genre naturally supports this—wrong turns get you killed, which organically prunes your story branches.

Avoiding Unfair Deaths

Deaths should feel earned, not arbitrary. Give readers warning signs. Make sure they understand why they died so failure teaches rather than frustrates. "You opened the door and a zombie bit you" is unfair. "You opened the door despite the scratching sounds" is a lesson.

Other Structural Patterns

Beyond the core branch-and-bottleneck and gauntlet approaches, several other narrative structures offer unique advantages for zombie stories:

- Time Cave: Heavy exponential branching with many distinct endings. While unsustainable for long-form narratives, this works brilliantly for short zombie survival vignettes—every choice matters, every path feels unique, but the scope remains manageable.

- Diamond: Branches diverge dramatically then converge at critical pinch points. In zombie contexts: reaching safehouses, surviving major horde encounters, day/night transitions. Readers experience different journeys but hit the same major story beats.

- Quest: Modular geography-focused clusters where each location (mall, hospital, suburb) is a self-contained mini-story with its own branching. Perfect for open-world zombie survival where readers choose which areas to explore.

- Open Map: Reversible travel between nodes—readers can move freely between discovered locations. Creates a sense of agency but requires careful state tracking to prevent narrative contradictions.

- Loop and Grow: Cycles through similar situations (daily supply runs, nightly defenses) that unlock new options each iteration as skills improve and resources accumulate. Great for base-building zombie survival stories.

- Floating Modules/Storylets: Quality-based narrative where encounters unlock based on character state rather than linear position. A "betrayal" encounter triggers when trust is low, regardless of location. Offers tremendous replayability but requires sophisticated state tracking.

Iconic Zombie Locations

Location shapes everything in zombie fiction—the resources available, the density of threats, the psychological atmosphere, and the thematic resonance. Understanding the narrative DNA of classic zombie settings helps you choose (or subvert) them effectively.

| Location | Origin | Narrative Use |

|---|---|---|

| Mall | Dawn of the Dead (1978) | Consumerism critique, abundant resources, siege mentality. The irony of wealth amid collapse. |

| Prison | The Walking Dead | Defensible architecture, ironic freedom/captivity reversal. Safety that becomes a trap. |

| Rural Farmhouse | Night of the Living Dead (1968) | Isolation, claustrophobia despite open space, limited resources. Nowhere to run. |

| Urban Wasteland | Various | Scale of destruction, scavenging gameplay, maze-like navigation. Civilization's corpse. |

| Military Base/Bunker | Various | False security, dark secrets, weapons cache. Authority that failed or corrupted. |

| Hospital | 28 Days Later, Walking Dead | Common outbreak origin, medical supplies, infected patients. Healing turned horrific. |

Location as Story Engine

Your setting choice cascades through every aspect of your narrative. A mall offers abundant food but attracts desperate survivors and hordes. A farmhouse means self-sufficiency but isolation from information. A military base promises weapons but raises questions about what the government did before it fell. Choose your location for what it enables narratively—the conflicts, resources, NPCs, and themes it naturally generates—not just for atmosphere.

Tracking Variables Instead of Branches

Rather than creating separate paths for every choice, track choices as variables that affect outcomes later. A Chapter 1 decision between "Brutality" and "Compassion" doesn't create two story branches—it sets a stat that determines how NPCs react in Chapter 5.

SURVIVAL: health, hunger, fatigue, infection_timer

RESOURCES: food, water, ammo, medicine, fuel

RELATIONSHIPS: sarah_trust, mike_loyalty, group_morale

STORY FLAGS: found_cure, knows_truth, spared_stranger

LOCATION: current_area, discovered_places[], safe_routes[]

// These affect outcomes without multiplying paths

Designing Meaningful Choices

A choice feels meaningful when the reader has enough information to decide thoughtfully and believes their decision changes something they care about. The best choices involve incomparable options—safety versus morality, logic versus loyalty—where there's no objectively "correct" answer.

The Safe / Risky / Wild Card Triad

A reliable template for structuring choices:

"Stay hidden until the horde passes"

> RISKY OPTION: Higher reward, potential for major loss, requires skill/resource

"Make a run for the supplies across the street"

> WILD CARD: Unpredictable, unique consequences, reveals new information

"Signal to the stranger on the roof"

Choice Frequency Guidelines

Offer reader interaction every 100-200 words. Avoid "walls of text" over 400 words without a choice. Even simple choices asking how the reader feels maintain engagement and establish that the story is listening.

| Scene Type | Words Between Choices | Options Per Choice |

|---|---|---|

| Action/Combat | 50-100 | 2-3 |

| Exploration | 150-200 | 3-4 |

| Dialogue | 100-150 | 3-4 |

| Quiet/Recovery | 200-300 | 2-3 |

Survival Mechanics

The best zombie CYOA makes readers feel the weight of survival. Tracking resources, health, and infection creates tension and forces meaningful trade-offs. Here are systems adapted from games like Project Zomboid and Resident Evil.

Health State Tracking

A simplified three-tier system works well for narrative pacing:

- HEALTHY: No penalties. Full range of options available.

- INJURED: -1 to physical actions. Some strenuous choices unavailable. "Your wounded leg slows you down."

- CRITICAL: -2 to all actions. Death risk on failed checks. Limited options. "Every step is agony. You're not sure how much longer you can keep going."

Infection Progression

Based on Project Zomboid's Knox infection model—a ticking clock that creates mounting dread:

| Stage | Timeline | Symptoms | Story Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | 0-6 hours | "Slight warmth in wound?" | Hidden from reader, can be hidden from group |

| Onset | 6-24 hours | Headache, cold sweats | Others may notice, -1 to checks |

| Progression | 24-48 hours | "Everything hurts" | Cannot hide it, -2 to checks, options limited |

| Terminal | 48+ hours | Vision blurs, thoughts fragment | Character dies unless cure exists |

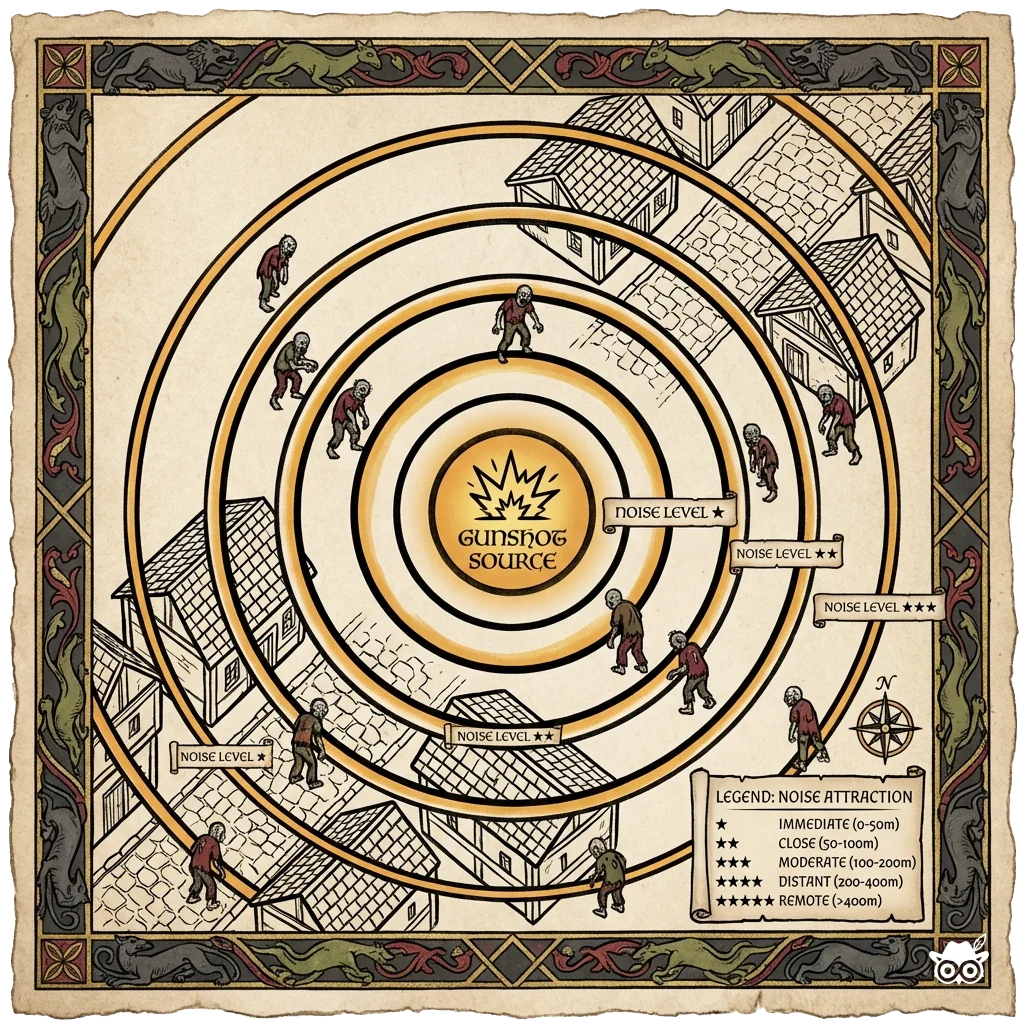

Noise Mechanics

Sound attracts zombies. This simple rule creates organic consequences for player choices and adds a layer of strategy to every encounter.

★☆☆☆☆ Silent — Sneaking, hand signals, careful movement

★★☆☆☆ Quiet — Whispered conversation, slow door opening

★★★☆☆ Moderate — Normal talking, breaking window carefully

★★★★☆ Loud — Shouting, car alarm, melee combat

★★★★★ Extreme — Gunfire, explosions, crashing vehicles

Track "Area Alert Level" (0-100%). At thresholds:

25% — Distant shuffling sounds

50% — Shapes moving toward the noise

75% — Dozen zombies converging

100% — Forced horde encounter

Characters in Zombie Fiction

Zombies are a force of nature. The actual story is always about the survivors—their relationships, conflicts, and the choices they make when civilization crumbles.

The Player Character

In CYOA, the protagonist is inhabited rather than performed. Define their capabilities and limitations, not their biography. Keep physical descriptions vague enough for reader projection. Focus on actions, reactions, and sensations rather than identity.

Essential NPC Archetypes

A normal person thrust into leadership by circumstances. Their arc: accepting responsibility, making impossible decisions, learning to inspire or failing to hold the group together.

Examples: Rick Grimes (Walking Dead), Shaun (Shaun of the Dead)

Story function: Central decision-maker, moral compass, or moral collapse

Someone hiding their infection from the group. Classic trope creating paranoia and forcing confrontation. Usually ends in tragedy—the question is how much damage they cause first.

Story function: Tension generator, forces group to confront infection rules, creates betrayal drama

Warning: Don't drag this out too long—readers will guess, and delayed reveals feel cheap.

Often more dangerous than the zombies. Someone who exploits chaos for power, resources, or darker urges. Represents what humanity becomes without civilization's restraints.

Examples: The Governor, Negan (Walking Dead)

Story function: Proves that humans are the real monsters, creates political/survival conflict

Seeks to understand or cure the outbreak. May have caused it. Source of exposition, hope, and sometimes horror when the truth is revealed.

Story function: Information delivery, cure subplot, potential villain reveal

Maintains humanity when others lose it. Challenges pragmatic decisions, insists on helping strangers, refuses to abandon the weak. May be the group's soul or its fatal weakness.

Story function: Creates tension with survival-focused characters, represents hope, tests reader's values

Relationship Mechanics

Track how NPCs feel about the protagonist using a simple numerical system:

0-19 Hostile — May actively work against you

20-39 Distrustful — Reluctant cooperation, withholds information

40-59 Neutral — Basic cooperation, no extras

60-79 Friendly — Active support, shares resources

80-100 Devoted — Will risk their life for you

// Separate tracks can add nuance:

TRUST: Do they believe what you say?

FEAR: Are they afraid of you?

LOYALTY: Will they stay under pressure?

Pacing Your Horror

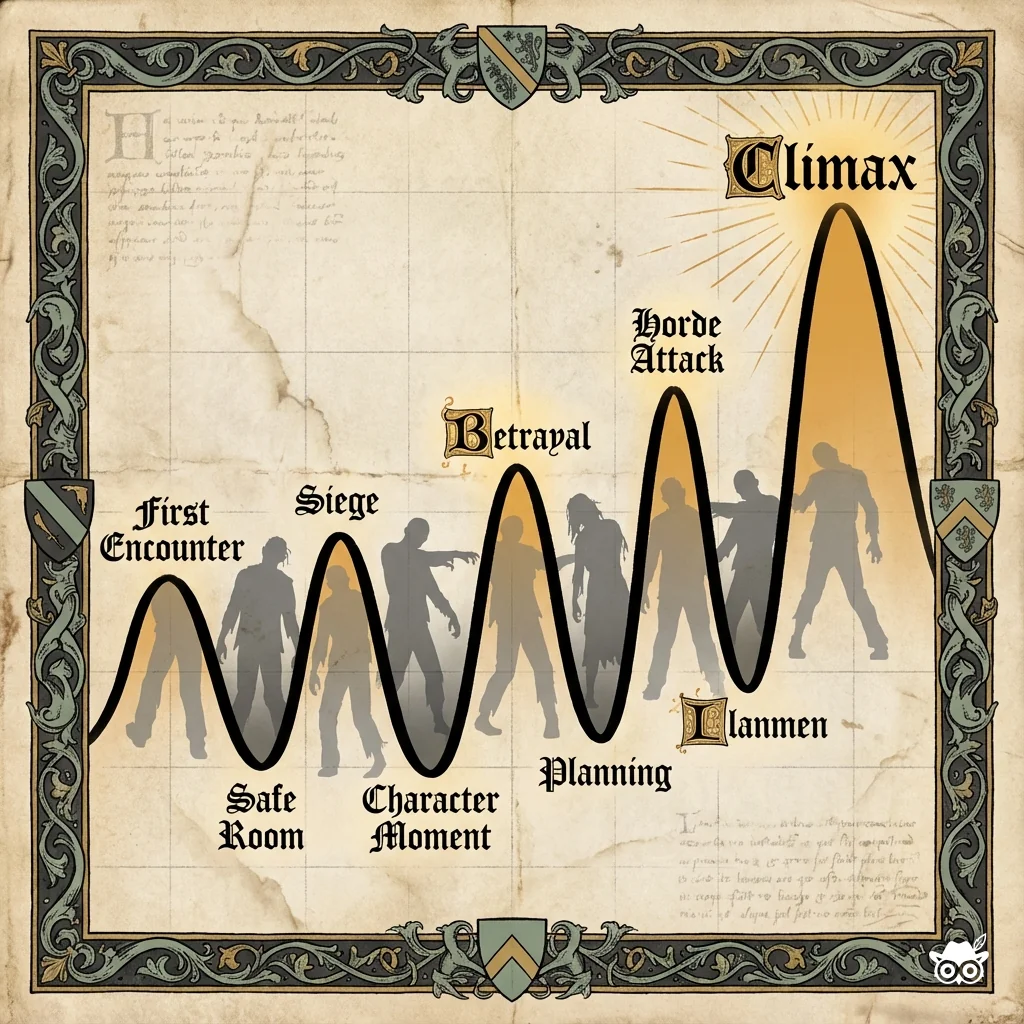

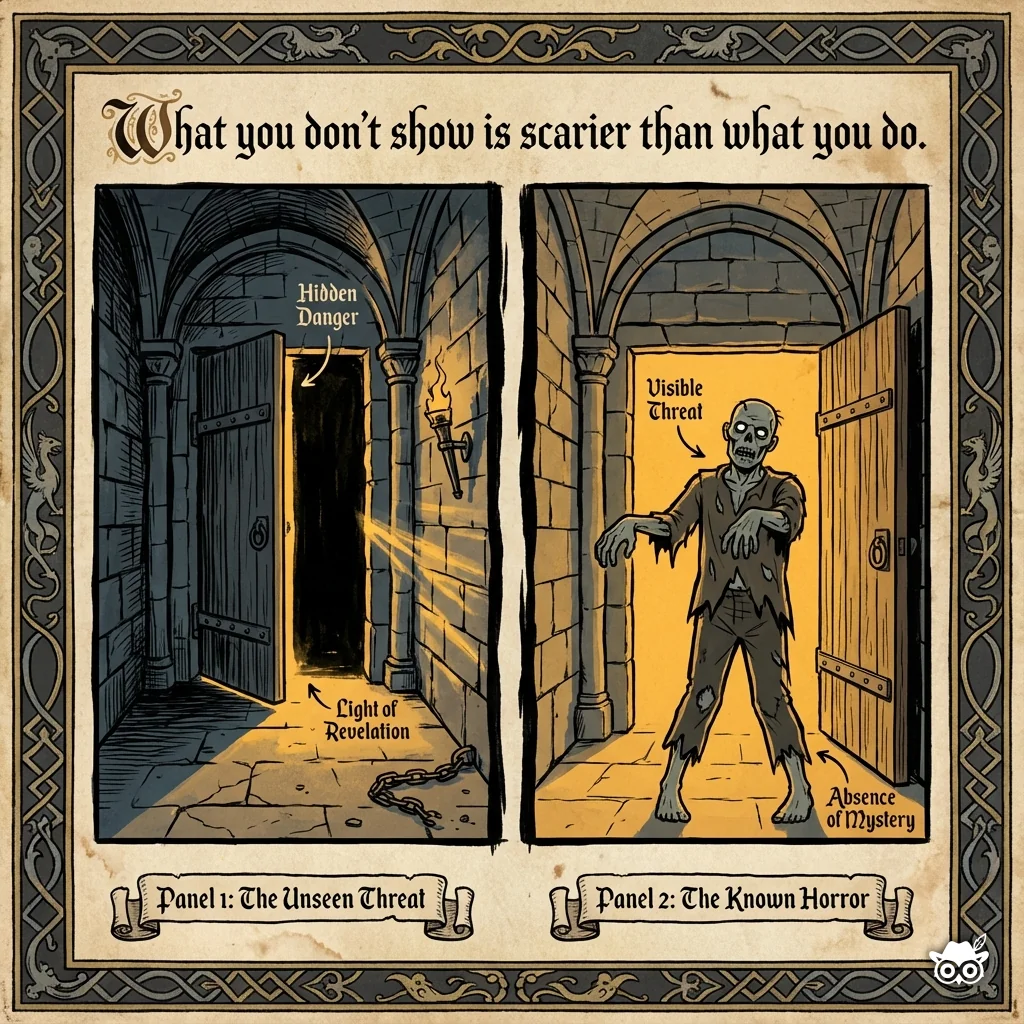

Constant tension exhausts readers. Constant safety bores them. Great zombie fiction follows a rhythm—peaks of terror followed by valleys of quiet that make the next peak hit harder.

The Roller Coaster Model

Action scenes are the drop; slow scenes are the climb. Save the largest drop for the climax, with smaller peaks building toward it. As Resident Evil 2's director explained: "Having nothing but tension throughout the whole game would be exhausting for players, so we designed save rooms as a safe place to take a breather."

The Function of Safe Rooms

Safe rooms in survival horror serve multiple purposes beyond just saving progress:

- Emotional release: The hope they represent makes the danger meaningful

- Pacing mechanism: Prevents reader exhaustion

- Strategic hub: Where plans are made and resources managed

- Paradoxical tension: Knowing you're safe makes you dread leaving

Never Break Safe Room Sanctity